Effect of Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollutants on Hospital Admissions for End-Stage Renal Disease Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

-

摘要:目的 评估接受维持性血液透析的终末期肾脏疾病(end-stage renal disease, ESRD)患者人群中,空气污染物短期暴露与每日入院次数的关联性。方法 本研究数据来源于中国西南某城市全市城镇职工基本医疗保险和城镇居民基本医疗保险数据库,纳入接受维持性血液透析治疗的ESRD患者。采用单一污染物和多污染物广义加性模型来估计不同滞后日空气污染物(CO、NO2、O3、PM10、PM2.5和SO2)对入院情况的影响。此外,按性别、年龄、PM2.5和PM10浓度阈值、季节、心血管疾病和高血压合并症等开展亚组分析。结果 单一污染物模型中,患者入院次数与显著相关的污染物及其对应的最强关联时间为:CO每增加0.1 mg/m3,滞后7 d的患者入院次数增加2.39%〔95%置信区间(confidence interval, CI):0.96%~3.83%〕;NO2、O3、PM2.5、PM10和SO2每增加10 μg/m3,患者入院次数分别在滞后7 d时增加4.02%(95%CI:1.21%~6.91%),滞后0~4 d时增加3.57%(95%CI:0.78%~6.44%),滞后6 d时增加2.00%(95%CI:1.07%~2.93%),滞后7 d时增加1.19%(95%CI:0.51%~1.88%),滞后7 d时增加8.37%(95%CI:3.08%~13.93%)。多污染物模型中,O3和PM2.5每增加10 μg/m3,患者每日入院次数分别在滞后0~4 d时增加3.18%(95%CI:0.34%~6.09%),滞后7 d时增加1.85%(95%CI:0.44%~3.28%)。此外,亚组分析显示季节、空气污染的严重程度和患者的共存疾病可能是环境空气污染与ESRD血液透析患者入院次数关联的效应修饰因素。结论 空气污染与ESRD血液透析患者入院次数密切相关。关联程度随季节、空气污染严重程度和患者合并疾病的不同而存在差异。Abstract:Objective To evaluate the association between short-term exposure to air pollutants of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on maintenance hemodialysis and the number of daily hospital admissions.Methods The data on hospitalizations were obtained from the database of the municipal Urban Employees' Basic Medical Insurance and Urban Residents' Basic Medical Insurance of a city in Southwest China. Single and multiple pollutant generalized additive models were utilized to estimate the effect of air pollutants (CO, NO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5, and SO2) on patient admissions after the lag time of different numbers of days. In addition, subgroup analyses stratified by sex, age, PM2.5 and PM10 concentration thresholds, seasonality, and comorbidity status for cardiovascular diseases and hypertension were conducted.Results In the single pollutant models, the pollutants significantly associated with patient admissions and the corresponding lag time of the strongest association were as follows, every time CO increased by 0.1 mg/m3, there was a 2.39% increase (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.96%-3.83%) in patient admissions after 7 days of lag time; every time NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10, and SO2 increased by 10 μg/m3, patient admissions increased by 4.02% (95% CI: 1.21%-6.91%) after 7 days of lag time, 3.57% (95% CI: 0.78%-6.44%) after 0-4 days of lag time, 2.00% (95% CI: 1.07%-2.93%) after 6 days of lag time, 1.19% (95% CI: 0.51%-1.88%) after 7 days of lag time, and 8.37% (95% CI: 3.08%-13.93%) after 7 days of lag time, respectively. In the multiple pollutant model, every time O3 and PM2.5 increased by 10 μg/m3, there was an increase of 3.18% (95% CI: 0.34%-6.09%) in daily patient admissions after 0-4 days of lag time and an increase of 1.85% (95% CI: 0.44%-3.28%) after 7 days of lag time. Furthermore, subgroup analyses showed that seasonality, the severity of air pollution, and patients' comorbidities might be the effect modifiers for the association between ambient air pollution and hospital admissions in ESRD patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis.Conclusion Air pollution is closely associated with hospital admissions in ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis and the strength of this association varies according to seasonality, the severity of air pollution, and patients’ status of comorbidities.

-

Keywords:

- Air pollution /

- Admission /

- Hemodialysis /

- End-stage renal disease /

- Association

-

终末期肾脏疾病(end-stage renal disease, ESRD)是人群重大健康问题之一,不仅显著增加过早死亡和心血管事件等不良事件风险[1],并且与医疗资源消耗和医疗支出升高等密切相关[2]。频繁住院是ESRD患者引起的主要医疗资源消耗负担来源之一[3]。我国ESRD患病人数连年攀升,这些患者中约80%采用维持性血液透析作为肾脏替代治疗方式[4],个人和社会同样面临因入院率升高导致医疗资源消耗和费用支出上涨的挑战。

值得关注的是,越来越多的证据表明,短期暴露于空气污染物与心律失常[5]、卒中[6]和肺炎[7]等急性病发作有关。此外,环境空气污染还可直接影响多种疾病的入院率,包括心血管疾病[7]、呼吸系统疾病[8]和神经系统疾病[9]等。在慢性肾脏病方面,WYATT等[10]发现了细颗粒物(particulate matter, PM)2.5浓度的升高会导致美国ESRD患者入院率和30 d再入院率的增加。然而,中国空气质量特征与美国有所差异;且根据已有研究,不同环境中空气污染物对健康的危害影响模式及程度亦存在显著差别[11]。因此,笔者认为,在ESRD患病率和接受维持性血液透析患者人数不断增长的背景下,基于我国环境和医学数据研究空气污染物对上述患者入院风险的影响,将有助于评价由不良环境暴露引起的额外ESRD疾病负担。故本研究基于中国西南地区医疗保险数据库的真实世界数据评估短期空气污染物暴露与ESRD血液透析患者入院次数之间的关联性及其强度。

1. 对象与方法

1.1 研究对象

本研究数据来源为中国四川省某城市全市城镇职工基本医疗保险和城镇居民基本医疗保险的数据库,时间跨度为2014年1月1日−12月31日。由于数据保密约定,本研究未披露城市名称,该数据库已被多项研究用于空气污染与疾病负担关系的评估[12-14]。

本研究纳入进行维持性血液透析的ESRD患者。根据该市当时医疗保险报销政策,维持性血液透析的医保医嘱可每3个月开立一次,因此采用以下纳入标准:①患者接受血液透析或血液透析滤过治疗3个月及以上;②血液透析治疗频率为3个月内至少12次。排除同时接受腹膜透析或既往曾行肾脏移植手术的患者。

1.2 暴露因素

1.2.1 环境数据

通过中国空气质量在线监测分析平台(https://www.aqistudy.cn/historydata)获取空气污染物每日浓度数据,包括一氧化碳(carbon monoxide, CO)、二氧化氮(nitrogen dioxide, NO2)、臭氧(O3,每日8 h滑动平均值)、PM2.5、PM10和二氧化硫(sulfur dioxide, SO2)。因本研究将同时研究空气污染物单日滞后及累积滞后的影响,因此纳入数据期限为2013年12月1日−2014年12月31日。

1.2.2 气象数据

收集2014年1月1日−12月31日期间来自中国国家气象信息中心(http://data.cma.cn/)的气温和相对湿度的每日测量数据。

1.3 结局指标

本研究临床结局为该市ESRD血液透析患者的每日入院人数。在数据库中根据入院时间和出院时间字段检索住院时长超过24 h的患者。按入院日期进行每日入院人数统计。

1.4 统计学方法

1.4.1 描述性分析与相关性分析

本研究中,如果连续变量符合正态分布,则用

$ \bar x \pm s $ 表示;否则用中位数(P25,P75)范围表示。此外,为了避免多重共线性问题,本研究采用Spearman相关分析对暴露因素进行相关性检验。1.4.2 统计模型构建

鉴于既往关于空气污染物的滞后效应研究显示,单日滞后(如:第1天、第2天等)和累积滞后(如:0~1 d、0~2 d等)均可能影响健康结局,因此,本研究同时采用单日和累积滞后水平构建模型,以探究空气污染物浓度与血液透析患者入院次数关联性最高的滞后天数。对单日暴露水平,滞后0 d被定义为从入院当天午夜开始的第一个24 h时段的空气污染物平均浓度,滞后1 d则为前一个24 h时段,以此类推。对累积日暴露水平,以滞后0 d和1 d的平均值表征滞后0~1 d污染物浓度,滞后0 d、1 d和2 d的平均值表征滞后0~2 d浓度,以此类推。

本研究首先在单污染物模型中采用广义加性模型和拟泊松回归分别对CO、NO2、O3、PM2.5、PM10和SO2等每项空气污染物与每日入院人数建模。使用准似然方法来校正过分散[15-16]。引入可能影响入院人次的“休息日和工作日”变量进行校正(三分类变量:周末或节假日,放假后第一个工作日,其他正常工作日)。此外,为排除日常气象条件的非线性混杂效应影响,模型还校正了平均温度和相对湿度的自然立方样条函数(自由度=3)[17]。按广义交叉验证(generalized cross-validation, GCV)误差最小值确定每种空气污染物最强效应对应的滞后日[18]。此后,本研究在多污染物模型中同时纳入所有空气污染物,选取其最强单变量效应滞后期对应的浓度,并校正混杂变量[15],以评价污染物与患者入院次数的独立关联性。

1.4.3 亚组分析与敏感性分析

为探究空气污染物与患者入院次数之间的关联是否在不同人群或环境中存在差异,本研究按以下分组进行了亚组分析:性别(男,女),年龄(≤65岁,>65岁)[19],PM2.5浓度(≤75 μg/m3,>75 μg/m3),PM10浓度(≤150 μg/m3,>150 μg/m3)[20],季节(冷季:10~3月,暖季:4~9月)[16],合并症(心血管疾病和高血压)。其中,心血管疾病和高血压合并症分别根据Elixhauser指数定义[21]。从数据库收集和记录患者出院ICD-10诊断,出院诊断为I09.9,I11.0,I13.0,I25.5,I42.0,I42.5,I42.6,I42.7,I42.8,I42.9,I43,I50,P29.0,I44.1,I44,2,I44.3,I45.6,I45.9,I47,I48,I49,R00.0,R00.1,R00.8,T82.1,Z45.0,Z95.0,A52.0,I05,I06,I07,I08,I09.1,I09.8,I34,I35,I36,I37,I38,I39,Q23.0,Q23.1,Q23.2,Q23.3,Z95.2,Z95.3,Z95.4,I26,I27,I28.0,I28.8或I28.9被定义为心血管疾病合并症,出院诊断为I10,I11,I12,I13或I15被定义为高血压合并症。

此外,采用双污染物模型进行敏感性分析以验证研究结果的鲁棒性。

1.4.4 统计评估方法

以相对危险度(relative risk, RR)和超额危险度〔excess relative risk, ERR;ERR=(RR-1)×100%〕及其95%置信区间(confidence interval, CI)表示每种空气污染物单位浓度变化(NO2、O3、PM2.5、PM10、SO2:每增加10 μg/m3,CO:每增加0.1 mg/m3)与每日入院人数的关联性[15]。通过Altman和Bland[22]描述的“z检验”评估亚组分析中不同人群和环境条件下空气污染与入院人数关联是否存在显著差异。双侧P值<0.05为差异有统计学意义。所有数据整理与分析使用R(3.5.1版)软件进行。

2. 结果

2.1 人群特征和环境指标描述

本研究纳入3787例接受维持性血液透析的ESRD患者,其中,男性2039例(53.84%),患者的年龄中位数(P25,P75)为57(44.5,69.5)岁。在研究期内共发生10745次入院记录,人均2.84次。

CO、NO2、O3、PM2.5、PM10和SO2的浓度分别为1.0(0.75,1.25) mg/m3,51.9(41.05,62.75) μg/m3,47.3(27.9,66.7) μg/m3,64.1(34.5,93.7) μg/m3,107.0(60.7,153.3) μg/m3和18.7(10.85,26.55) μg/m3。温度的中位数为17.8(11.6,24.0)℃,相对湿度的平均值为(76.11±9.11)%,见表1。

表 1 医院入院人群特质、空气污染物和气象变量的描述统计Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the number of hospital admissions, air pollutants, and meteorological variablesVariable Median (P25, P75) or $ \bar x \pm s $ Air pollutant concentration (24-hour mean) CO/(mg/m3) 1.0 (0.75, 1.25) NO2/(μg/m3) 51.9 (41.05, 62.75) O3 (8-hour mean)/(μg/m3) 47.3 (27.9, 66.7) PM2.5/(μg/m3) 64.1 (34.5, 93.7) PM10/(μg/m3) 107.0 (60.7, 153.3) SO2/(μg/m3) 18.7 (10.85, 26.55) Meteorological measures (24-hour mean) Temperature/℃ 17.8 (11.6, 24) Relative humidity/% 76.11±9.11 Daily maintenance HD hospitalization 9 (0, 18) Sex Men 5 (0, 10) Women 5 (1, 9) Age ≤65 yr. 7 (1, 13) >65 yr. 4 (0.5, 7.5) PM2.5 and PM10 levels PM2.5≤75 μg/m3 10 (0, 20) PM2.5>75 μg/m3 8 (0, 16) PM10≤150 μg/m3 9 (0, 18) PM10>150 μg/m3 8 (0.5, 15.5) Season† Cold season 9 (0, 18) Warm season 8 (0, 16) Comorbidities With CVD 1 (0.5, 1.5) Without CVD 9 (0, 18) With hypertension 1 (0.5, 1.5) Without hypertension 9 (0, 18) HD: hemodialysis; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CO: carbon monoxide; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; O3: ozone; PM2.5: particular matter with an aerodynamic diameter≤2.5 μm; PM10: particular matter with an aerodynamic diameter≤10 μm; SO2: sulfur dioxide. † Cold season: From October to March; Warm season: from April to September. 2.2 空气污染物浓度和气象指标的相关性分析

对空气污染物浓度和气象指标之间进行Spearman相关性分析,观察到PM10和PM2.5之间高度正相关(r=0.97,P<0.0001),见表2。

表 2 各暴露因素间的Spearman相关系数Table 2. Spearman correlation coefficients between the exposure factorsFactor CO NO2 O3 PM2.5 PM10 SO2 Temp RH CO 1.00 0.69 −0.48 0.74 0.67 0.61 −0.48 0.06 NO2 * 1.00 −0.32 0.72 0.73 0.65 −0.33 −0.27 O3 * * 1.00 −0.31 −0.30 −0.33 0.75 −0.38 PM2.5 * * * 1.00 0.97 0.67 −0.49 −0.18 PM10 * * * * 1.00 0.69 −0.50 −0.30 SO2 * * * * * 1.00 −0.44 −0.20 Temp * * * * * * 1.00 −0.08 RH * * * * * 1.00 Temp: temperature; RH: relative humidity. The other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. * P<0.05, which indicates that the correlation between two variables is significant at the 0.05 level. 2.3 单污染物模型不同滞后时间效应分析

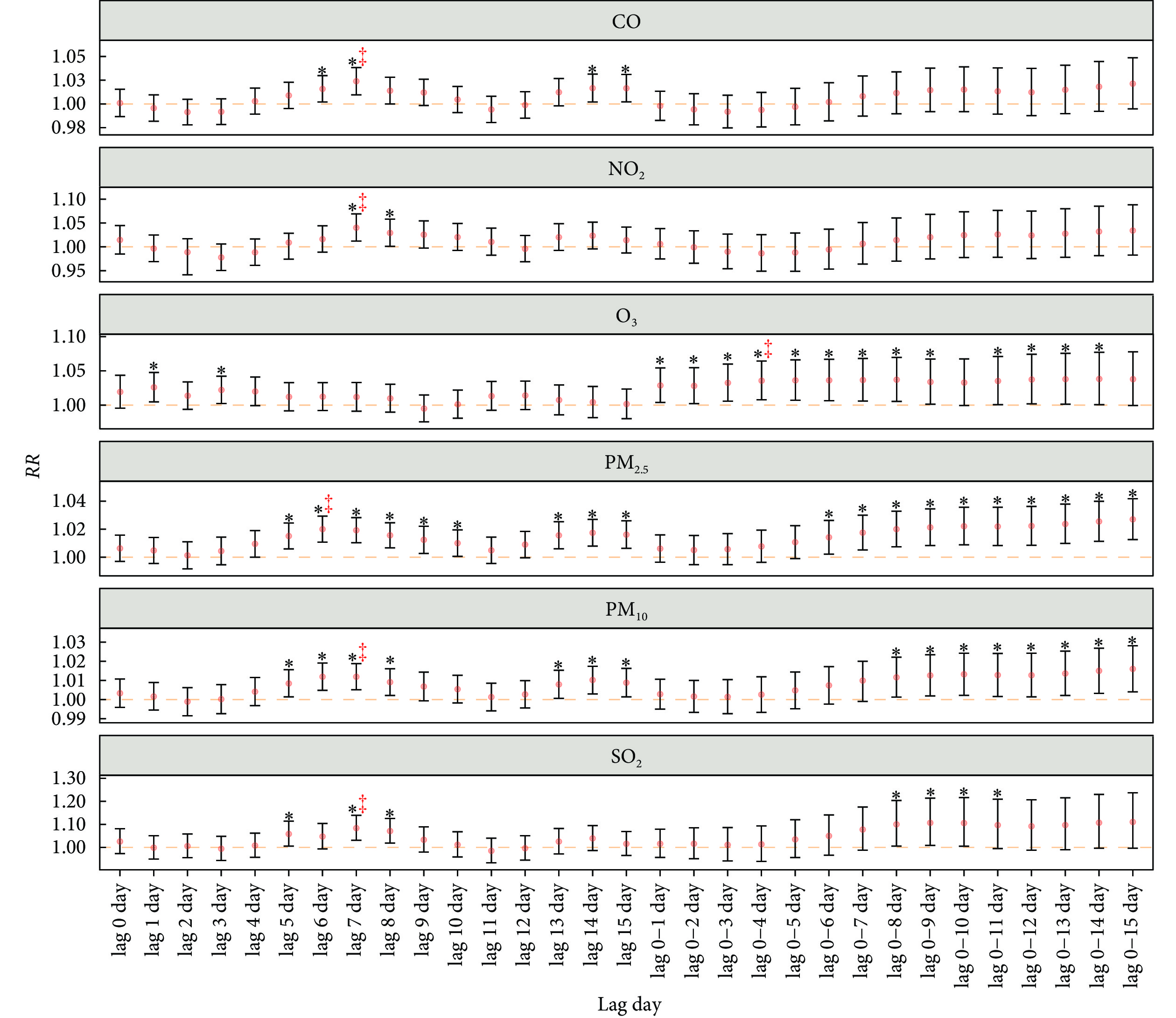

单污染物模型结果表明,每日入院人数与不同空气污染物关联的效应大小和最强关联出现的时间存在差异(图1)。每个污染物浓度均与入院人数显著相关,其中CO的最强效应出现在单日滞后7 d(每增加0.1 mg/m3,每日入院人数增加2.39%,95%CI:0.96%~3.83%),NO2的最强效应出现在单日滞后7 d(每增加10 μg/m3,每日入院人数增加4.02%,95%CI:1.21%~6.91%),O3的最强效应出现在累积滞后0~4 d(每增加10 μg/m3,每日入院人数增加3.57%,95%CI:0.78%~6.44%),PM2.5的最强效应出现在单日滞后6 d(每增加10 μg/m3,每日入院人数增加2.00%,95%CI:1.07%~2.93%),PM10的最强效应出现在单日滞后7 d(每增加10 μg/m3,每日入院人数增加1.19%,95%CI:0.51%~1.88%),SO2的最强效应出现在单日滞后7 d(每增加10 μg/m3,每日入院人数增加8.37%,95%CI:3.08%~13.93%)。

![]() 图 1 单污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险Figure 1. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the single-pollutant modelsRR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line represents the horizontal line with 1 value for RR. * P <0.05. ‡ represents the lag day of the most significant association for each air pollutant on the single-pollutant model.

图 1 单污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险Figure 1. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the single-pollutant modelsRR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line represents the horizontal line with 1 value for RR. * P <0.05. ‡ represents the lag day of the most significant association for each air pollutant on the single-pollutant model.2.4 多污染物模型下空气污染物浓度对每日入院人数的风险分析

多污染物模型结果显示,O3在累积滞后0~4 d的浓度和PM2.5在滞后6 d的浓度下,每日入院人数分别显著增加3.18%(95%CI:0.34%~6.09%)和1.85%(95%CI:0.44%~3.28%),见表3。

表 3 多污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的每日入院人数之间的相关风险Table 3. Relative risk for the associations between air pollutants and increased admissions in the multi-pollutant modelsParameter Air pollutant CO NO2 O3 PM2.5 PM10 SO2 Best lag day/d 7 7 0-4 6 7 7 RR (95% CI) 1.02 (0.99-1.04) 0.98 (0.93-1.02) 1.03 (1.00-1.06) 1.02 (1.00-1.03) 0.99 (0.98-1.00) 1.06 (0.99-1.13) RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. 2.5 基于不同季节、PM2.5水平与合并症的亚组分析

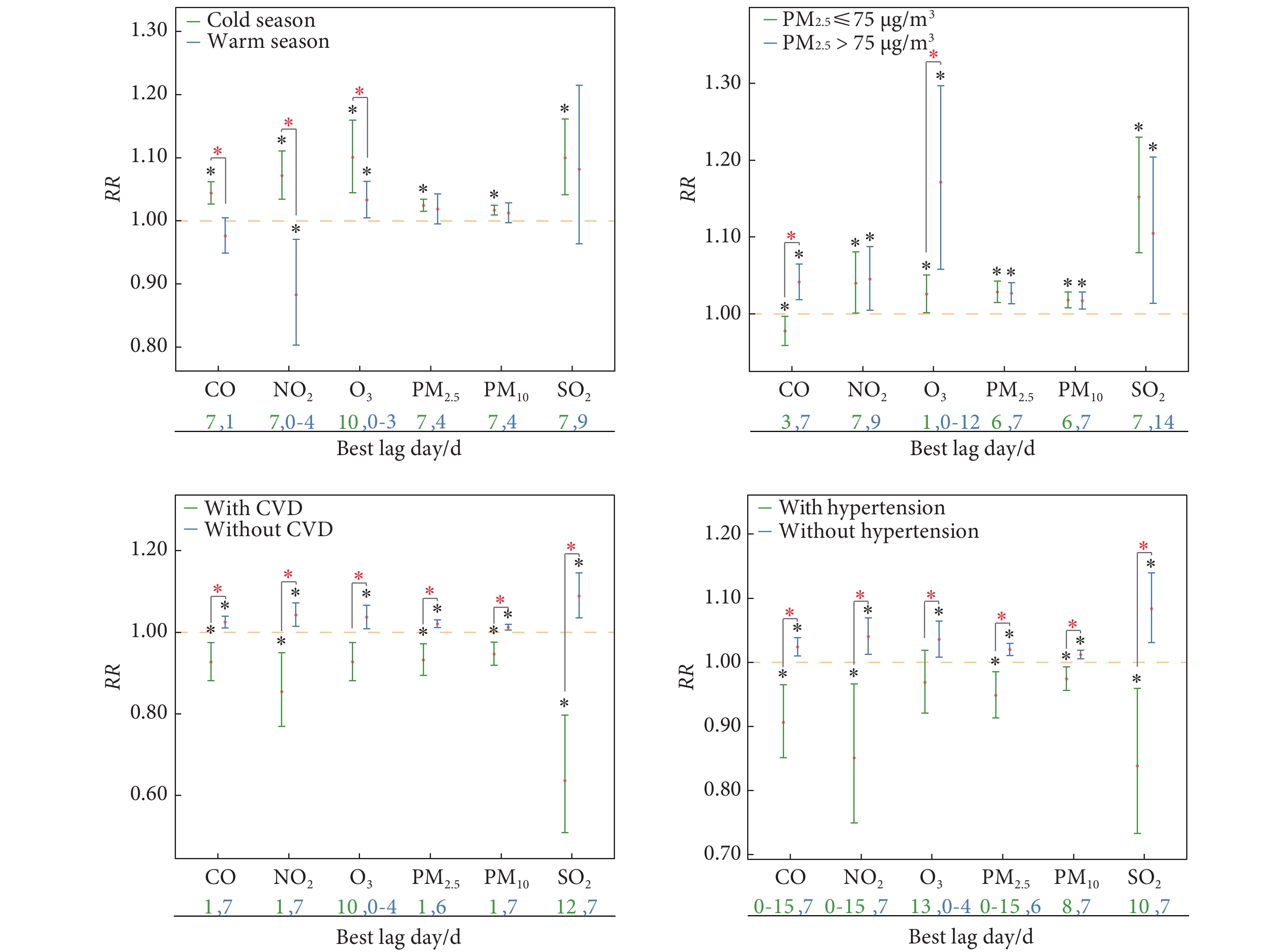

亚组分析显示,空气污染物水平与血液透析患者的关联性在不同季节、PM2.5水平和合并症(心血管疾病和高血压)中存在差异,见图2。例如,在冷季中,CO、NO2和O3的关联比暖季更强,CO和O3的效应在PM2.5浓度>75 μg/m3和PM2.5浓度≤75 μg/m3时亦出现显著差异,不同的空气污染物在患有或未患有心血管疾病以及高血压共病者中所产生的效应也存在差异。

![]() 图 2 不同亚组分析中空气污染物与医院入院次数增加的相关风险Figure 2. Relative risk for the associations between air pollutants and increased admissions in subgroup analysesRR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval, with the two different colors of the error bars representing the two subgroups compared . The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. The numbers below each subfigure are the the lag day of the most significant association for the specific air pollutant in the single-pollutant model. Black *, P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model with the best lag day. Red * , P<0.05, indicates that there is significant difference in the RR of the maintenance hemodialysis admissions for corresponding air pollutant effect between the compared subgroups. Cold season: From October to March; Warm season: from April to September.

图 2 不同亚组分析中空气污染物与医院入院次数增加的相关风险Figure 2. Relative risk for the associations between air pollutants and increased admissions in subgroup analysesRR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval, with the two different colors of the error bars representing the two subgroups compared . The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. The numbers below each subfigure are the the lag day of the most significant association for the specific air pollutant in the single-pollutant model. Black *, P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model with the best lag day. Red * , P<0.05, indicates that there is significant difference in the RR of the maintenance hemodialysis admissions for corresponding air pollutant effect between the compared subgroups. Cold season: From October to March; Warm season: from April to September.2.6 双污染物模型下空气污染物浓度对入院人数影响的敏感性分析

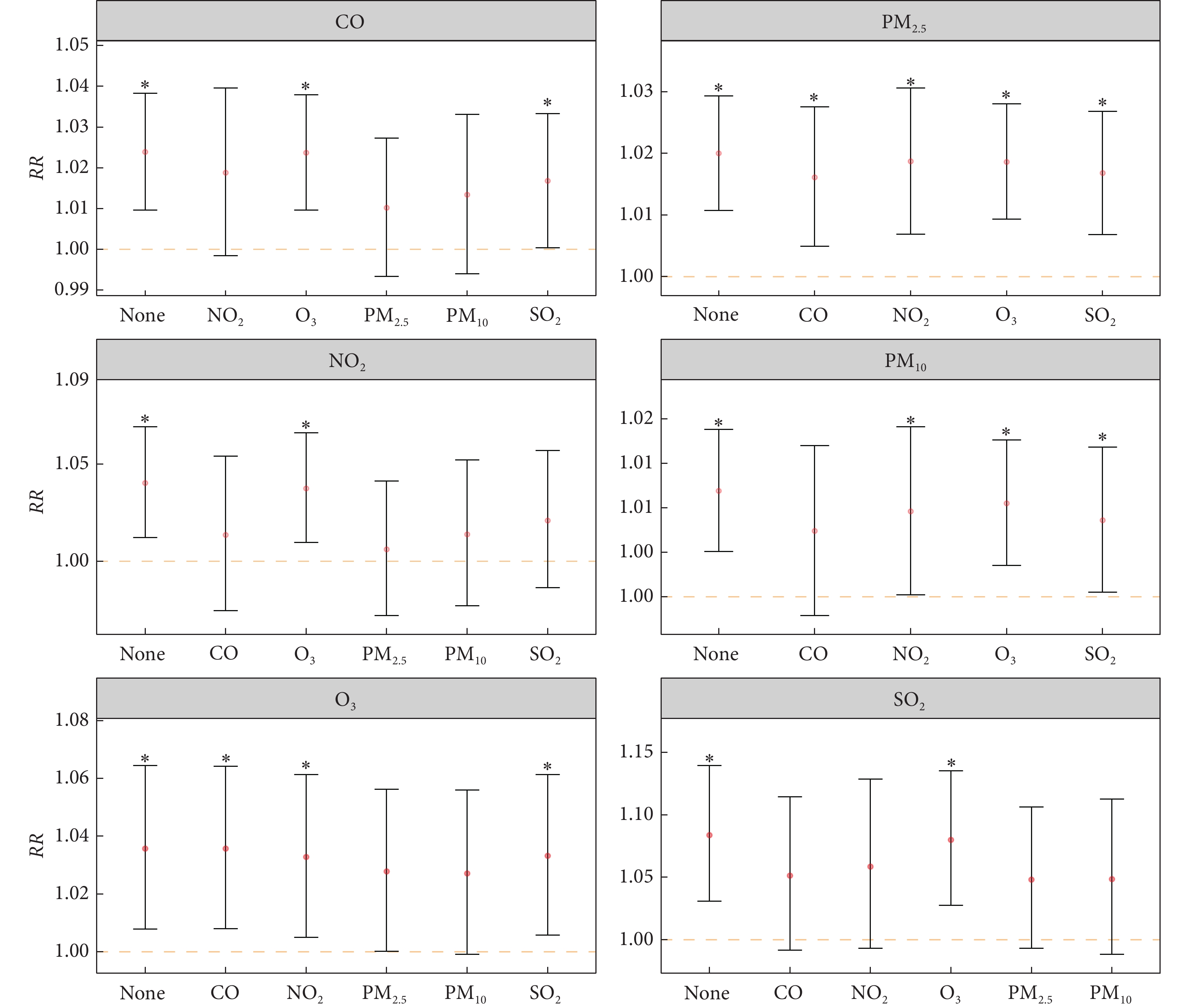

结果(图3)显示,在模型中加入另一种空气污染物后,每种空气污染物的RR降低或相等。例如,每10 μg/m3 O3增加对于医院入院次数的RR从1.04降至1.03,且在调整PM10后,O3不再与入院次数独立相关。然而,在调整其他空气污染物后,PM2.5与医院入院次数的关联仍然显著。鉴于前述的高度相关性,未对PM2.5和PM10进行双污染物模型分析。

![]() 图 3 双污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险Figure 3. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the bi-pollutant modelsThe abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. * P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model (as represented by ‘None’ on the x-axis) or the two-pollutant model.

图 3 双污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险Figure 3. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the bi-pollutant modelsThe abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. * P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model (as represented by ‘None’ on the x-axis) or the two-pollutant model.3. 讨论

本研究发现,O3和PM2.5等空气污染物浓度与ESRD血液透析患者每日入院次数增加密切相关。其关联程度在多种条件下存在差异,例如秋冬季节或春夏季节、PM2.5水平高低和患者的共存疾病等。

当前越来越多的证据表明环境空气污染与肾脏疾病发病及其并发症有关。例如,PM2.5与膜性肾病的风险呈正相关[23];PM10可对估计肾小球滤过率下降和慢性肾脏疾病患病率产生潜在影响[24];腹膜透析患者暴露于较高浓度NO2,其2年死亡率升高[25];美国的ESRD患者中环境PM2.5与心血管入院风险增加有关[10]。本研究细致评估了空气污染物对我国ESRD维持性血液透析患者入院人次的效应。首先,开展单污染物模型分析,以确定与入院次数显著相关的单污染物及其影响最为显著的单日时间点或累积日时间段。其次,构建多污染物模型,同时引入第一步中确定的污染物显著滞后时间对应的浓度,发现O3和PM2.5是维持透析患者入院的独立风险因素。第三,考虑到空气污染物之间可能存在共线性,进一步在双污染物模型中验证了O3和PM2.5的影响,发现当其他污染物被纳入双污染物模型中时,O3和PM2.5与每日入院人数几乎保持稳定,但是当PM10被引入O3的模型中时,O3的影响会有所下降。笔者认为,该研究结果可以推广到与中国具有相似空气质量特征的国家与地区。

本研究发现空气污染物和维持性血液透析患者入院次数之间显著相关,结果与高血压[26]、哮喘[27]和慢性阻塞性肺疾病[28]等其他疾病中关于入院风险的研究类似。这可能与急性暴露于空气污染物导致的机体改变有关,如O3可能升高血清ACE和ET-1水平并改变脂质代谢[29],PM暴露与系统性炎症和氧化应激、动脉粥样硬化等相关[30],这些病理生理改变可能直接引发血液透析患者需紧急入院照护的病症。此外,由于O3和PM2.5等诱发的急性疾病(如心血管意外、全身感染等)亦可能增加ESRD患者入院的风险,在一定程度上解释了污染物与HD患者入院之间的关联。

本研究的另一个重要发现是季节性、空气质量和心血管疾病共病可能影响环境空气污染与入院治疗之间的关联强度。PM2.5与入院治疗的关联在温季并不明显,而O3的风险与入院治疗的关联在寒季更强,但仅限于PM2.5浓度≤75 μg/m3。这些结果表明,空气污染物与温度和PM浓度具有交互作用。此外,合并心血管疾病和高血压的患者中,O3和PM2.5对入院风险的影响显著高于没有这些疾病的患者。这些发现提示,在寒冷季节、PM2.5污染加重等环境中,需要额外关注ESRD血液透析患者的病情变化,尤其是同时合并心血管疾病的病患。

本研究的局限性主要包括:本研究关注环境空气污染物短期暴露的效应,未对中、长期暴露可能产生的影响进行校正。受数据可及性限制,本研究未对医生入院指征差异等潜在混杂因素进行校正。本研究来源于单一城市医保数据,未来仍需大样本前瞻性队列对结果进行进一步验证。本研究采用2014年数据进行分析,尽管针对维持性血液透析的医保报销政策及临床指南对于透析频次的推荐未发生重大变化,但不同年份空气质量存在差异,不同空气质量背景下污染物对入院风险的影响值得持续开展研究。

综上,空气污染物浓度与我国ESRD血液透析患者入院次数密切相关,这种关联的强度在多种情况下存在差异,如季节性变化、空气污染严重程度和患者合并症等。

* * *

作者贡献声明 陈一龙负责正式分析、调查研究、研究方法、可视化、初稿写作和审读与编辑写作,胡耀负责数据审编和审读与编辑写作,詹宇和李春漾负责审读与编辑写作,孙雅婧和辜永红负责研究项目管理和审读与编辑写作,曾筱茜负责论文构思、经费获取、研究方法、监督指导、验证和审读与编辑写作。所有作者已经同意将文章提交给本刊,且对将要发表的版本进行最终定稿,并同意对工作的所有方面负责。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

-

图 1 单污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险

Figure 1. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the single-pollutant models

RR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line represents the horizontal line with 1 value for RR. * P <0.05. ‡ represents the lag day of the most significant association for each air pollutant on the single-pollutant model.

图 2 不同亚组分析中空气污染物与医院入院次数增加的相关风险

Figure 2. Relative risk for the associations between air pollutants and increased admissions in subgroup analyses

RR: relative risk; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval, with the two different colors of the error bars representing the two subgroups compared . The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. The numbers below each subfigure are the the lag day of the most significant association for the specific air pollutant in the single-pollutant model. Black *, P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model with the best lag day. Red * , P<0.05, indicates that there is significant difference in the RR of the maintenance hemodialysis admissions for corresponding air pollutant effect between the compared subgroups. Cold season: From October to March; Warm season: from April to September.

图 3 双污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的入院人数之间的相关风险

Figure 3. Relative risk for the association between air pollutants and increased admissions in the bi-pollutant models

The abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. The red points indicate RR and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The orange dash line indicates the RR value of 1. * P<0.05, indicates that the effect of air pollutants on maintenance hemodialysis admissions is statistically significant in the single-pollutant model (as represented by ‘None’ on the x-axis) or the two-pollutant model.

表 1 医院入院人群特质、空气污染物和气象变量的描述统计

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the number of hospital admissions, air pollutants, and meteorological variables

Variable Median (P25, P75) or $ \bar x \pm s $ Air pollutant concentration (24-hour mean) CO/(mg/m3) 1.0 (0.75, 1.25) NO2/(μg/m3) 51.9 (41.05, 62.75) O3 (8-hour mean)/(μg/m3) 47.3 (27.9, 66.7) PM2.5/(μg/m3) 64.1 (34.5, 93.7) PM10/(μg/m3) 107.0 (60.7, 153.3) SO2/(μg/m3) 18.7 (10.85, 26.55) Meteorological measures (24-hour mean) Temperature/℃ 17.8 (11.6, 24) Relative humidity/% 76.11±9.11 Daily maintenance HD hospitalization 9 (0, 18) Sex Men 5 (0, 10) Women 5 (1, 9) Age ≤65 yr. 7 (1, 13) >65 yr. 4 (0.5, 7.5) PM2.5 and PM10 levels PM2.5≤75 μg/m3 10 (0, 20) PM2.5>75 μg/m3 8 (0, 16) PM10≤150 μg/m3 9 (0, 18) PM10>150 μg/m3 8 (0.5, 15.5) Season† Cold season 9 (0, 18) Warm season 8 (0, 16) Comorbidities With CVD 1 (0.5, 1.5) Without CVD 9 (0, 18) With hypertension 1 (0.5, 1.5) Without hypertension 9 (0, 18) HD: hemodialysis; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CO: carbon monoxide; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; O3: ozone; PM2.5: particular matter with an aerodynamic diameter≤2.5 μm; PM10: particular matter with an aerodynamic diameter≤10 μm; SO2: sulfur dioxide. † Cold season: From October to March; Warm season: from April to September. 表 2 各暴露因素间的Spearman相关系数

Table 2 Spearman correlation coefficients between the exposure factors

Factor CO NO2 O3 PM2.5 PM10 SO2 Temp RH CO 1.00 0.69 −0.48 0.74 0.67 0.61 −0.48 0.06 NO2 * 1.00 −0.32 0.72 0.73 0.65 −0.33 −0.27 O3 * * 1.00 −0.31 −0.30 −0.33 0.75 −0.38 PM2.5 * * * 1.00 0.97 0.67 −0.49 −0.18 PM10 * * * * 1.00 0.69 −0.50 −0.30 SO2 * * * * * 1.00 −0.44 −0.20 Temp * * * * * * 1.00 −0.08 RH * * * * * 1.00 Temp: temperature; RH: relative humidity. The other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. * P<0.05, which indicates that the correlation between two variables is significant at the 0.05 level. 表 3 多污染物模型中空气污染物与增加的每日入院人数之间的相关风险

Table 3 Relative risk for the associations between air pollutants and increased admissions in the multi-pollutant models

Parameter Air pollutant CO NO2 O3 PM2.5 PM10 SO2 Best lag day/d 7 7 0-4 6 7 7 RR (95% CI) 1.02 (0.99-1.04) 0.98 (0.93-1.02) 1.03 (1.00-1.06) 1.02 (1.00-1.03) 0.99 (0.98-1.00) 1.06 (0.99-1.13) RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval; the other abbreviations are explained in the note to Table 1. -

[1] HEMMELGARN B R, MANNS B J, LLOYD A, et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA,2010,303(5): 423–429. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2010.39

[2] VANHOLDER R, ANNEMANS L, BROWN E, et al. Reducing the costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care: a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol,2017,13(7): 393–409. DOI: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.63

[3] SARAN R, ROBINSON B, ABBOTT K. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis,2019,73(3 Suppl 1): A7–A8. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.001

[4] LI P K, LUI S L, NG J K, et al. Addressing the burden of dialysis around the world: a summary of the roundtable discussion on dialysis economics at the First International Congress of Chinese Nephrologists 2015. Nephrology,2017,22(Suppl 4): 3–8. DOI: 10.1111/nep.13143

[5] LIU X, KONG D, LIU Y, et al. Effects of the short-term exposure to ambient air pollution on atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol,2018,41(11): 1441–1446. DOI: 10.1111/pace.13500

[6] SUN S, STEWART J D, ELIOT M N, et al. Short-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of stroke in the Women's Health Initiative. Enviro Int,2019,132: 105065. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105065

[7] ZHANG W, LIN S, HOPKE P K, et al. Triggering of cardiovascular hospital admissions by fine particle concentrations in New York state: Before, during, and after implementation of multiple environmental policies and a recession. Environ Pollut,2018,242(Pt B): 1404–1416. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.030

[8] DOMINICI F, PENG R D, BELL M L, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA,2006,295(10): 1127–1134. DOI: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127

[9] CULQUI D R, LINARES C, ORTIZ C, et al. Association between environmental factors and emergency hospital admissions due to Alzheimer's disease in Madrid. Sci Total Environ,2017,592: 451–457. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.089

[10] WYATT L H, XI Y, KSHIRSAGAR A, et al. Association of short-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 with hospital admissions and 30-day readmissions in end-stage renal disease patients: population-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open,2020,10(12): e041177. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041177

[11] WHO Regional Office for Europe. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution--REVIHAAP Project: technical report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013: 301.

[12] YONG Z, LUO L, GU Y, et al. Bayesian comorbidity network and cost analysis for asthma. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform,2022,26(9): 4714–4724. DOI: 10.1109/JBHI.2022.3182368

[13] ZENG S, LUO L, CHEN F, et al. Association of outdoor air pollution with the medical expense of ischemic stroke: the case study of an industrial city in western China. Int J Health Plann Manage,2021,36(3): 715–728. DOI: 10.1002/hpm.3115

[14] YONG Z, LUO L, GU Y, et al. Implication of excessive length of stay of asthma patient with heterogenous status attributed to air pollution. J Environ Health Sci Eng,2021,19(1): 95–106. DOI: 10.1007/s40201-020-00584-8

[15] KO F W, TAM W, WONG T W, et al. Effects of air pollution on asthma hospitalization rates in different age groups in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Allergy,2007,37(9): 1312–1319. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02791.x

[16] CAI J, ZHAO A, ZHAO J, et al. Acute effects of air pollution on asthma hospitalization in Shanghai, China. Environ Pollut,2014,191: 139–144. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.04.028

[17] PASCAL M, FALQ G, WAGNER V, et al. Short-term impacts of particulate matter (PM10, PM10–2. 5, PM2.5) on mortality in nine French cities. Atmospheric Environment,2014,95: 175–184. DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.06.030

[18] KLOT S V, ZANOBETTI A, SCHWARTZ J. Influenza epidemics, seasonality, and the effects of cold weather on cardiac mortality. Environ Health,2012,11: 74. DOI: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-74

[19] WHO. Influenza (Seasonal). https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (2018).

[20] Ministry of Environmental Protection AoQSaIQ. Ambient air quality standards (GB3095-2012), http://english.mee.gov.cn/Resources/standards/Air_Environment/quality_standard1/201605/W020160511506615956495.pdf (2012, accessed August 28 2019).

[21] ELIXHAUSER A, STEINER C, HARRIS D R, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical Care,1998,36(1): 8–27. DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

[22] ALTMAN D G, BLAND J M. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ,2003,326(7382): 219. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219

[23] YANG Y R, CHEN Y M, CHEN S Y, et al. Associations between long-term particulate matter exposure and adult renal function in the Taipei metropolis. Environ Health Perspect,2017,125(4): 602–607. DOI: 10.1289/EHP302

[24] LIN J H, YEN T H, WENG C H, et al. Environmental NO2 level is associated with 2-year mortality in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Medicine (Baltimore),2015,94(1): e368. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000368

[25] XU X, WANG G, CHEN N, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and increased risk of membranous nephropathy in China. J Am Soc Nephrol,2016,27(12): 3739–3746. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2016010093

[26] SONG J, LU M, LU J, et al. Acute effect of ambient air pollution on hospitalization in patients with hypertension: a time-series study in Shijiazhuang, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf,2019,170: 286–292. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.125

[27] LU P, ZHANG Y, LIN J, et al. Multi-city study on air pollution and hospital outpatient visits for asthma in China. Environ Pollut,2020,257: 113638. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113638

[28] RAJI H, RIAHI A, BORSI S H, et al. Acute effects of air pollution on hospital admissions for asthma, COPD, and bronchiectasis in Ahvaz, Iran. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis,2020,15: 501–514. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S231317

[29] XIA Y, NIU Y, CAI J, et al. Effects of personal short-term exposure to ambient ozone on blood pressure and vascular endothelial function: a mechanistic study based on DNA methylation and metabolomics. Environ Sci Technol,2018,52(21): 12774–12782. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03044

[30] HAMANAKA R B, MUTLU G M. Particulate matter air pollution: effects on the cardiovascular system. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne),2018,9: 680. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00680

开放获取 本文遵循知识共享署名—非商业性使用4.0国际许可协议(CC BY-NC 4.0),允许第三方对本刊发表的论文自由共享(即在任何媒介以任何形式复制、发行原文)、演绎(即修改、转换或以原文为基础进行创作),必须给出适当的署名,提供指向本文许可协议的链接,同时标明是否对原文作了修改;不得将本文用于商业目的。CC BY-NC 4.0许可协议详情请访问 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0

首页

首页

下载:

下载: