-

摘要:目的 探讨程序性死亡配体-1(programmed death ligand-1, PD-L1)在坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis, NEC)小鼠模型中的表达和作用。方法 采用野生型C57BL/6J小鼠20只,随机分入对照组与造模组,对照组母乳喂养,造模组采用脂多糖+配方奶喂养+缺氧+冷刺激的方法进行NEC诱导,随后取小鼠肠道进行HE染色评估病理改变、免疫荧光共定位检测PD-L1表达定位、Western blot检测肠道PD-L1表达量,并取外周血进行流式分析检测白细胞亚群及其PD-L1表达;取PD-L1(+/+)与PD-L1(−/−)小鼠各14只,随机分入各自基因型对照组与造模组,诱导方法同前,取小鼠肠道进行HE染色评估病理改变,取外周血检测炎症因子表达。结果 成功构建NEC小鼠模型,PD-L1在小鼠肠道中表达于肠上皮细胞及炎症细胞,在外周血中表达于T细胞、单核细胞、中性粒细胞;NEC小鼠肠道PD-L1表达较对照组增加,NEC小鼠外周血中T细胞、单核细胞比例及其PD-L1表达较对照组无明显变化,中性粒细胞比例及其PD-L1表达较对照组分别增加约140%和150%(P<0.05);PD-L1基因小鼠实验结果显示,对照组PD-L1(+/+)小鼠与PD-L1(−/−)小鼠肠道情况及血清炎症因子水平无明显差异;PD-L1(−/−)NEC小鼠较PD-L1(+/+)NEC小鼠肠道病理改变加重,平均病理评分增加(P<0.05),同时PD-L1(−/−)NEC小鼠较PD-L1(+/+)NEC小鼠血清白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-10下降约44%、趋化因子配体1/IL-6/IL-1β均有25%以上的上升(P均<0.05)。结论 PD-L1在小鼠中广泛表达于炎症细胞和肠上皮细胞,敲除PD-L1加重了NEC小鼠的炎症反应与肠道病变程度,PD-L1在NEC发病中发挥减轻炎症反应的保护作用,其机制可能与调控中性粒细胞/肠上皮细胞有关。

-

关键词:

- 细胞程序性死亡配体-1 /

- 坏死性小肠结肠炎 /

- 小鼠模型 /

- 炎症因子

Abstract:Objective To investigate the expression and role of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in a mouse model of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).Methods A total of 20 wild-type C57BL/6J mice were randomly assigned to the control and the model groups. Mice in the control group were breastfed, while mice in the model group were given lipopolysaccharide, formula feeding, hypoxia, and cold stimulation for NEC induction. Then, the intestines of the mice were collected in order to assess the pathological changes through HE staining, to examine PD-L1 expression and localization with immunofluorescence co-localization, and to evaluate intestinal PD-L1 expression with Western blot. Peripheral blood was collected for flow cytometry to examine leukocyte subpopulations and their PD-L1 expression. On the other hand, 14 PD-L1 (+/+) mice and 14 PD-L1 (−/−) mice were randomly divided into their respective genotype control groups and model groups. The same induction method as was already mentioned was adopted for the model groups. The intestines of the mice were collected for HE staining to evaluate the pathological change and peripheral blood was collected to examine the expression of inflammatory factors.Results The NEC mouse model was successfully constructed. PD-L1 was widely expressed in enterocytes and inflammatory cells in the mouse intestines and in T cells, monocytes, and neutrophils in peripheral blood. The expression of PD-L1 in NEC mouse intestines increased in comparison with that of the control group. In the peripheral blood of NEC mice, the proportion of T cells and monocytes and their PD-L1 expression showed no significant changes compared with those of the control group, while the proportion of neutrophils and their PD-L1 expression increased by about 140% and 150%, respectively, in comparison with those of the control group (P<0.05). According to the results of the PD-L1 gene mouse experiment, the control groups of PD-L1 (+/+) mice and PD-L1 (−/−) mice showed no significant difference in their intestinal conditions and serum inflammatory factor levels, while the PD-L1 (−/−) NEC mouse had worse intestinal pathological changes and increased mean pathological scores compared with those of PD-L1 (+/+) NEC mouse (P<0.05). In addition, serum interleukin (IL)-10 in PD-L1 (−/−) NEC mouse decreased by about 44% compared with that of PD-L1 (+/+) NEC mice, and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1/IL-6/IL-1β all increased by more than 25% (all P<0.05).Conclusion PD-L1 is widely expressed in inflammatory cells and enterocytes in mice. Knocking out PD-L1 aggravates the degree of NEC inflammation and intestinal pathological changes. PD-L1 plays a protective role by reducing inflammation in the pathogenesis of NEC, the mechanism of which may be related to the regulation of neutrophils/enterocytes.-

Keywords:

- PD-L1 /

- Necrotizing enterocolitis /

- Mouse model /

- Inflammatory factor

-

坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis, NEC)是一种以小肠结肠斑片状坏死为主要特征的胃肠道致死性疾病[1-2],在早产儿中尤为多见[3-4]。随着早产儿救治技术的进步,早产儿存活率不断增加,NEC的发生率也呈现逐渐升高的趋势[4-5]。由于缺乏特异性的诊治措施,NEC的死亡率高达15%~30%[6-7]。虽然已有研究发现早产、感染、缺氧、配方奶喂养是NEC发病的主要危险因素[8],细菌感染引发失控的炎症反应是NEC发生的主要环节[9],但是对其具体调控机制仍有待深入。

程序性死亡受体配体-1(programmed death ligand-1, PD-L1)是介导机体免疫抑制的共刺激因子之一,广泛表达于B细胞、巨噬细胞等炎症细胞以及多种上皮细胞[10-11]。目前对PD-L1在炎症调节中的作用研究尚无统一定论。有文章指出在败血症中PD-L1表达增加抑制炎症细胞分泌干扰素-γ(interferon, IFN-γ)、白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-2等炎症因子[12],并抑制败血症患者外周血中PD-L1阳性的中性粒细胞和单核细胞的吞噬以及分泌功能[13],但是也有研究报道在败血症动物模型中阻断PD-L1信号通路改善了肠道上皮细胞功能并减少了IL-2、IL-6等炎症因子的分泌[14]。在慢性炎症性肠病中,有文章指出PD-L1的表达增加能减轻组织损伤[15],但是也有研究报道PD-L1抑制剂减少了肠道T细胞、巨噬细胞的浸润,IL-2、IFN-γ等炎症因子的分泌也降低,肠道炎症得到改善[16]。

NEC是一种以异常激活的炎症反应为发生发展关键环节的疾病,结合目前PD-L1的研究情况,我们推测PD-L1可能参与了NEC的发生发展,但目前国内外尚无相关研究。因此本研究采用小鼠建立NEC模型,对PD-L1在NEC小鼠模型中的表达进行研究,并利用PD-L1基因缺失小鼠进行NEC模型诱导后,分析PD-L1缺失对小鼠发病的影响,旨在探讨PD-L1在NEC发生发展中的作用及其可能的机制。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 实验动物

C57BL/

6J小鼠(SPF级)购自四川大学实验动物中心,于四川大学华西科技园实验动物中心按SPF级标准饲养、繁育,环境温度(23±2) ℃,白天/黑夜循环12 h更替,每笼小鼠数量不超过5只。 PD-L1(+/−)小鼠(C57BL/6JGpt-CD274em1Cd302d12132/Gpt)购自江苏集萃康生物科技有限公司,于四川大学华西科技园实验动物中心饲养、繁育,饲养条件同前。获得子代小鼠后剪取鼠尾、提取DNA、利用PCR技术鉴定基因型,筛选出PD-L1(+/+)基因型小鼠与PD-L1(−/−)基因型小鼠。

动物实验经过四川大学华西医院动物实验伦理委员会审查,符合四川省医学实验动物管理委员会的要求(医字第24101108号)。

1.2 主要试剂

新生儿奶粉购自美国Abbott company公司,动物山羊奶粉购自美国ESBILAC公司,脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS)购自美国Sigma公司,大鼠抗小鼠LY-6G单抗、大鼠抗小鼠CD45单抗、大鼠抗小鼠CD14单抗、大鼠抗小鼠PD-1(CD279)单抗、大鼠抗小鼠PD-L1(CD274)、大鼠抗小鼠CD3单抗均购自美国BD Biosciences公司,兔抗小鼠PD-L1抗体与山羊抗兔荧光二抗购自美国Thermo Scientific公司,大鼠抗小鼠CD45抗体与山羊抗大鼠荧光二抗购自英国Abcam公司,兔抗PD-L1多抗购自美国Thermo Scientific公司,兔抗β-actin购自日本TaKaRa公司,辣根过氧化物酶山羊抗兔抗体购自美国Santa Cruz公司,细胞因子试剂盒〔趋化因子配体1(chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligand 1, CXCL-1)/IL-6/IL-10/IL-1β〕购自美国R&D 公司。

1.3 小鼠分组及处理

4日龄C57BL/6J小鼠,不分雌雄,体质量2~2.5 g,随机分入造模组与对照组,每组10只,共20只。造模组于上午用自制灌胃器给予脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS)灌胃1次(约50 μL,2.5 mg/mL),30 min后给予缺氧-复氧刺激,随后将小鼠置于4 ℃冰箱进行冷刺激,下午给予第二轮相同的处理,期间间隔2~3 h给予代乳品灌胃(约60 μL/次)。上述操作连续重复3 d。对照组小鼠与母鼠同笼,母乳喂养,定期观察。取材时,对照组小鼠体质量约3.5~4 g,造模组小鼠体质量约1.5~2 g,乙醚麻醉小鼠后摘除眼球取得外周血,颈椎脱臼法处死小鼠后取肠道标本。

4日龄PD-L1(+/+)小鼠与PD-L1(−/−)小鼠,不分雌雄,体质量2~2.5 g,分别随机分入各自基因型的造模组与对照组,共4组,每组7只,总计28只。造模组与对照组处理方法同上。

1.4 小鼠肠道组织病理学检查与评分

用颈椎脱臼法处死小鼠后,取末段回肠置于体积分数为10%的甲醛固定液中,随后进行脱水、石蜡包埋、切片,常规HE染色。按照病理评分标准[17]进行评分。0分:肠道绒毛及上皮完整,组织结构正常;1分:轻度黏膜下或固有层肿胀分离;2分:中度黏膜下和/或固有层肿胀分离,黏膜下和/或肌层水肿;3分:重度黏膜下和/或固有层分离,黏膜下和/或肌层水肿,局部绒毛脱落;4分:肠绒毛消失伴肠坏死。评分时,采用双人盲评,每个样本取5个视野,计算平均值作为最终评分。≥2分视为NEC发病(造模成功的判定标准),评分越高,病变越重。

1.5 免疫荧光检测小鼠肠道组织PD-L1表达

将肠道石蜡切片脱蜡透明后,用PBS清洗并进行抗原修复;疏水笔画圈后滴加羊血清封闭30 min;孵育一抗(PD-L1抗体,浓度1∶400;CD45抗体,工作浓度1∶500),4 ℃过夜;PBS清洗后,滴加荧光二抗(工作浓度1∶1000),37 ℃孵育30 min,随后PBS清洗,避光重复2次;滴加足量细胞核染料DAPI(工作浓度1∶800)室温孵育5 min,随后PBS清洗;甘油封片后荧光显微镜采集图像。本实验按照试剂说明书推荐,采用脾脏组织作为阳性对照,绿色代表PD-L1蛋白,红色代表CD45蛋白(本实验中CD45为白细胞标志物),蓝色代表细胞核。

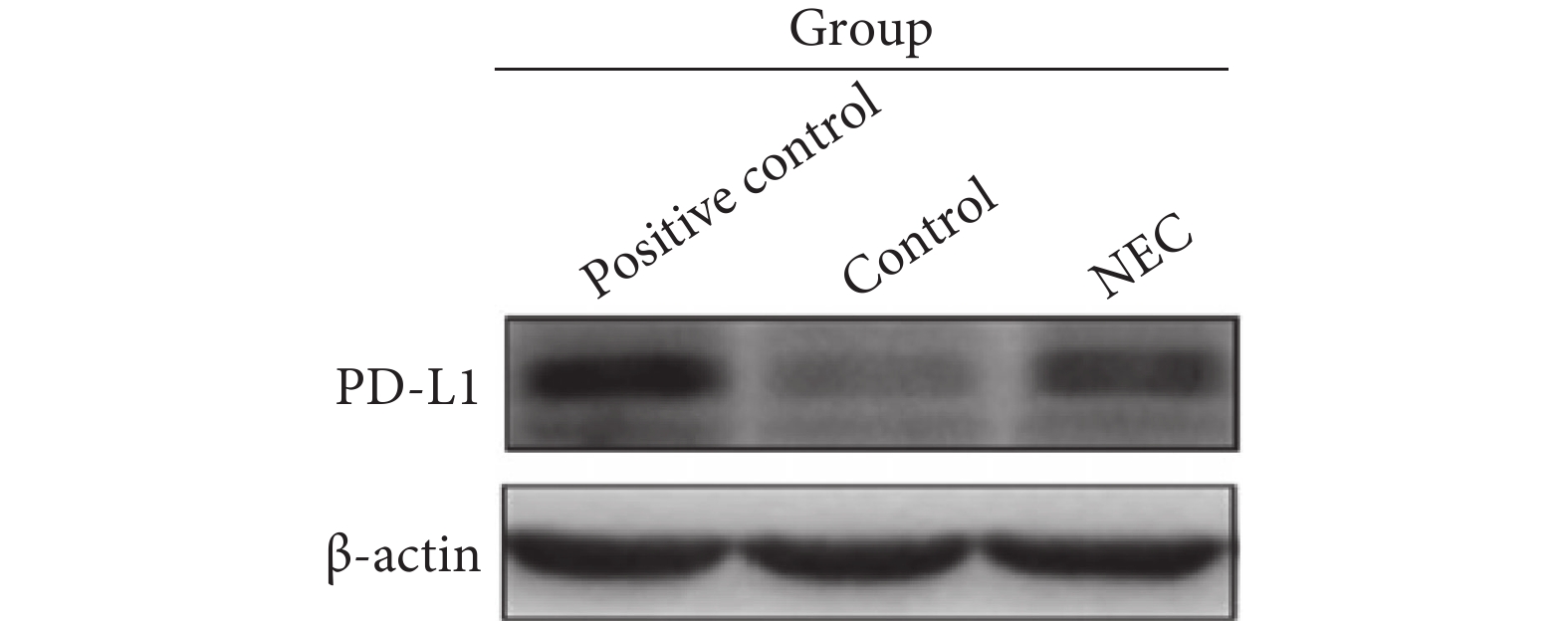

1.6 Western blot检测小鼠肠道PD-L1表达

称取适量回肠末段组织后,提取全蛋白,BCA法测定蛋白浓度。每组各取20 μg样本进行电泳,电泳后转膜、封闭、加入一抗(PD-L1抗体浓度以1∶800稀释,β-actin抗体以1∶3000稀释)。4 ℃摇床过夜后,加入二抗,显影剂显影,采用Image Lab软件分析目的条带的灰度值,以目的条带灰度值与内参条带灰度值的比值作为目的蛋白的相对表达量。本实验选取小鼠脾脏组织作为阳性对照。

1.7 流式细胞术检测小鼠外周血PD-L1表达

乙醚麻醉小鼠后摘除眼球取得外周血(约200 μL),加入红细胞裂解液裂解红细胞;离心分离白细胞,用试剂盒自带的专用缓冲液重悬;加入Fc受体阻断剂封闭5 min,随后加入目标抗体混合液,置于冰盒内避光孵育45 min;FBS反复清洗后,用流式细胞分析仪(cytoFlex流式细胞分析仪,Beckman coulter company,美国)检测。本实验对白细胞(CD45:FITC)、中性粒细胞(LY-6G:PE-Cy7)、T淋巴细胞(CD3:Percp-cy5.5)、单核细胞(CD14:APC-Cy7)及PD-L1(CD274:APC)进行检测。

1.8 液相芯片检测小鼠血清炎症因子

乙醚麻醉小鼠后摘除眼球取外周血(约200 μL),4 ℃静置2 h,离心分离血清(约30 μL);在96微孔板上逐孔加入缓冲液,摇晃混匀后吸除;加入抗体混合液,随后分别加入50 μL标准品和待检测样品(不足50 μL的样品稀释至50 μL并记录稀释倍数)孵育2 h;清洗3次后加入稀释的生物素-抗体混合物孵育1 h;清洗后加入链霉亲和素-PE,孵育30 min;用缓冲液重悬微粒后运行luminex200液相芯片检测仪检测。本实验检测CXCL1、IL-6、IL-10和IL-1β四种炎症因子。

1.9 统计学方法

定量数据以

$ \bar x \pm s$ 表示。数据先检验正态性与方差齐性,对于符合要求的两两比较采用t检验、多组比较采用单因素方差分析,不符合要求的数据采用Mann-Whitney U检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。2. 结果

2.1 野生型小鼠NEC模型构建

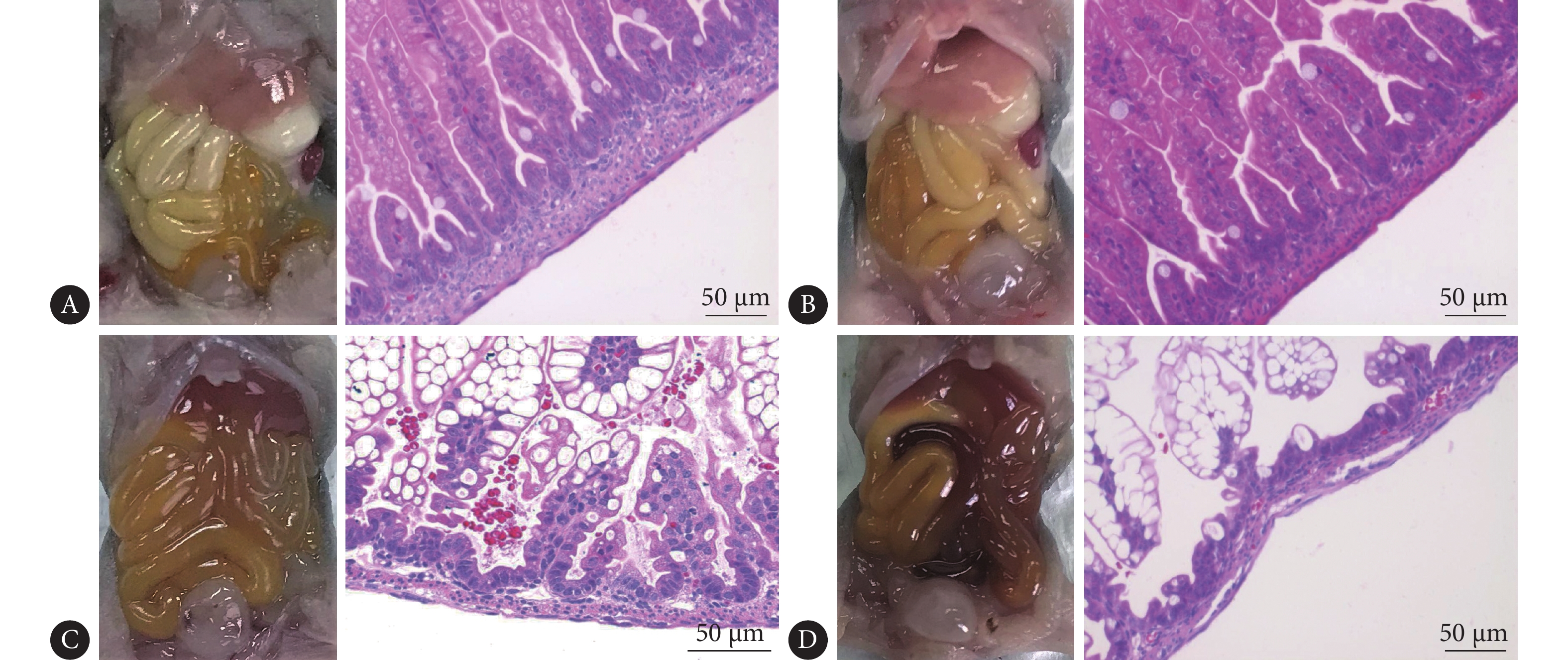

结果显示,肠道外观上,与对照组相比(图1A),造模组肠道充血、颜色暗淡,有肠道积气(图1C)。肠道HE染色可见:对照组肠道绒毛密集、绒毛柱长且完整,黏膜层、黏膜下层及肌层连接紧密(图1B);造模组肠道绒毛参差不齐、排列紊乱,部分绒毛水肿、脱落,黏膜层及黏膜下层水肿分离,可见炎症细胞浸润(图1D)。肠道病理改变评分:对照组为(0.12±0.14)分,造模组为(2.31±0.41)分,造模组评分高于对照组(P<0.01)。按病理评分标准,评分≥2分视为NEC发病,因此NEC模型诱导成功率为88.9%(8/9;1只小鼠因死于灌胃失误,未能完成实验全程,统计时未予计入)。

2.2 野生型小鼠肠道PD-L1的表达定位

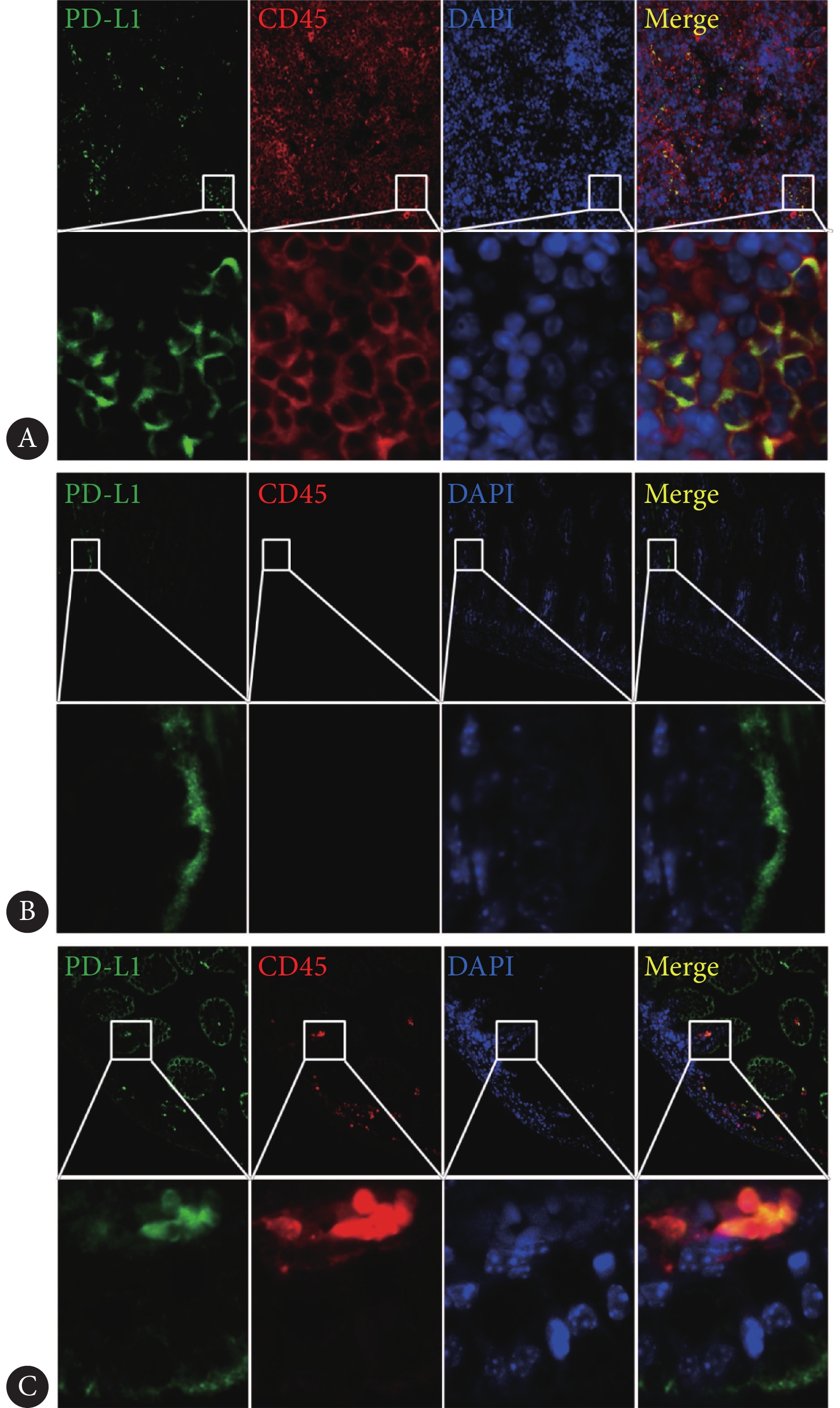

通过与CD45抗体的共定位发现,阳性对照脾脏的PD-L1呈簇状表达于白细胞上(图2A)。在母乳喂养小鼠肠道中,PD-L1主要表达于肠道绒毛上皮细胞(图2B),而在NEC小鼠肠道中,PD-L1表达于肠绒毛上皮细胞及肠壁浸润的白细胞上(图2C)。

![]() 图 2 PD-L1蛋白在野生型小鼠肠道的定位。×400(上排图片放大倍数)Figure 2. Localization of PD-L1 protein in the intestines of wild-type mice.×400 (magnification of the upper image)A: The spleen tissue (PD-L1+ control); B: Intestines of the control group; C: Intestines of NEC group. Green represents the PD-L1 protein, red represents the CD45 protein, and blue represents the nucleus.

图 2 PD-L1蛋白在野生型小鼠肠道的定位。×400(上排图片放大倍数)Figure 2. Localization of PD-L1 protein in the intestines of wild-type mice.×400 (magnification of the upper image)A: The spleen tissue (PD-L1+ control); B: Intestines of the control group; C: Intestines of NEC group. Green represents the PD-L1 protein, red represents the CD45 protein, and blue represents the nucleus.2.3 野生型小鼠肠道PD-L1蛋白的表达水平

结果显示(图3),NEC小鼠病变肠道的PD-L1蛋白表达水平(0.433±0.106)较母乳喂养小鼠肠道(0.336±0.675)增加,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

2.4 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞PD-L1的表达

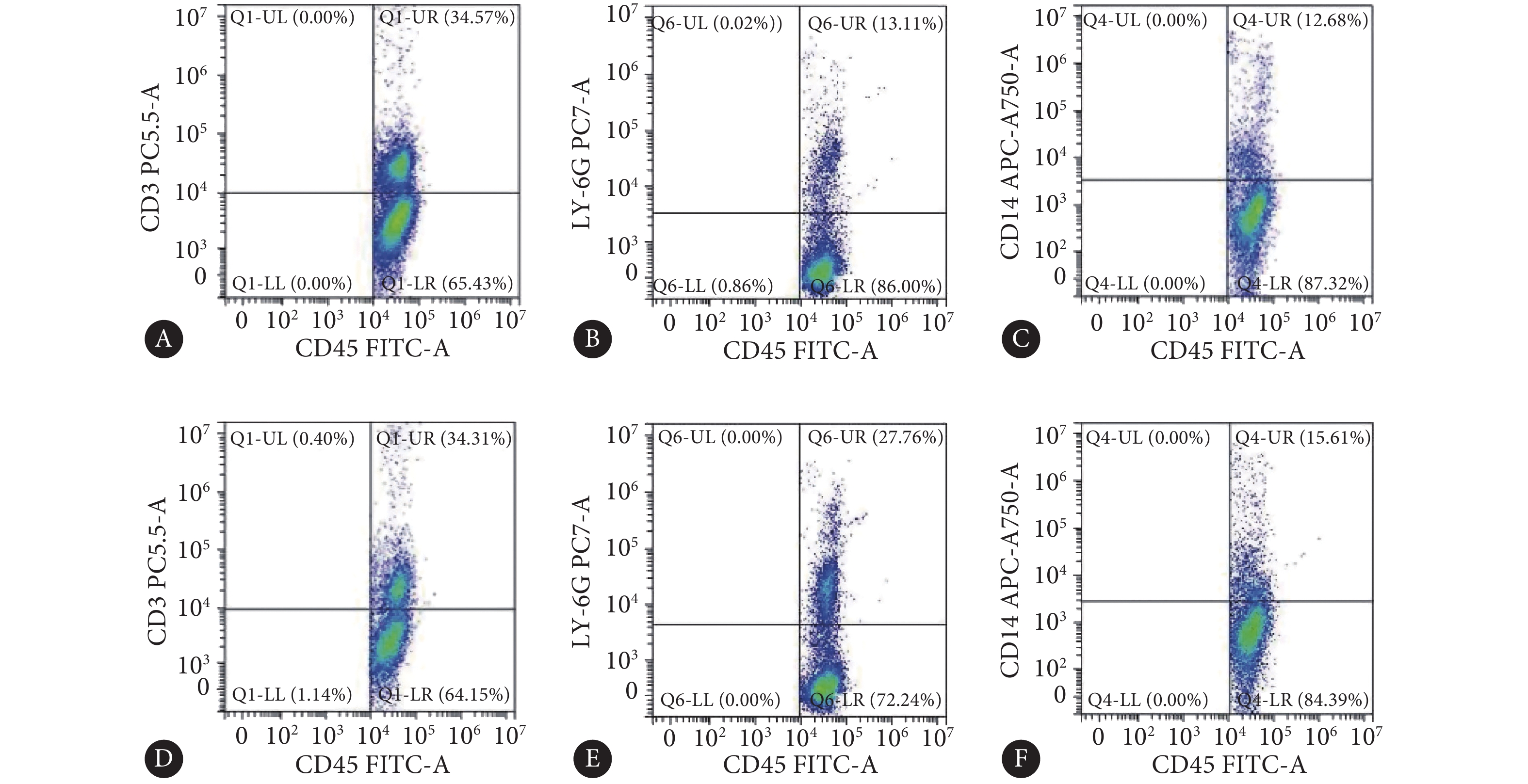

对照组小鼠外周血T淋巴细胞、中性粒细胞、单核细胞占白细胞比例(%)分别为33.54±3.88、11.52±2.35、11.89±2.54;造模组小鼠外周血T淋巴细胞、中性粒细胞、单核细胞占白细胞比例(%)分别为32.78±5.28、27.84±4.02、14.34±3.03,其中中性粒细胞比例较对照组增加约140%(P<0.05)(图4)。

![]() 图 4 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群占总白细胞比例Figure 4. Proportion of leukocyte subsets in total leukocytes in the peripheral blood of wild-type miceA: T cells in the control group; B: Neutrophils in the control group; C: Monocytes in the control group; D: T cells in NEC group; E: Neutrophils in NEC group; F: Monocytes in NEC group.

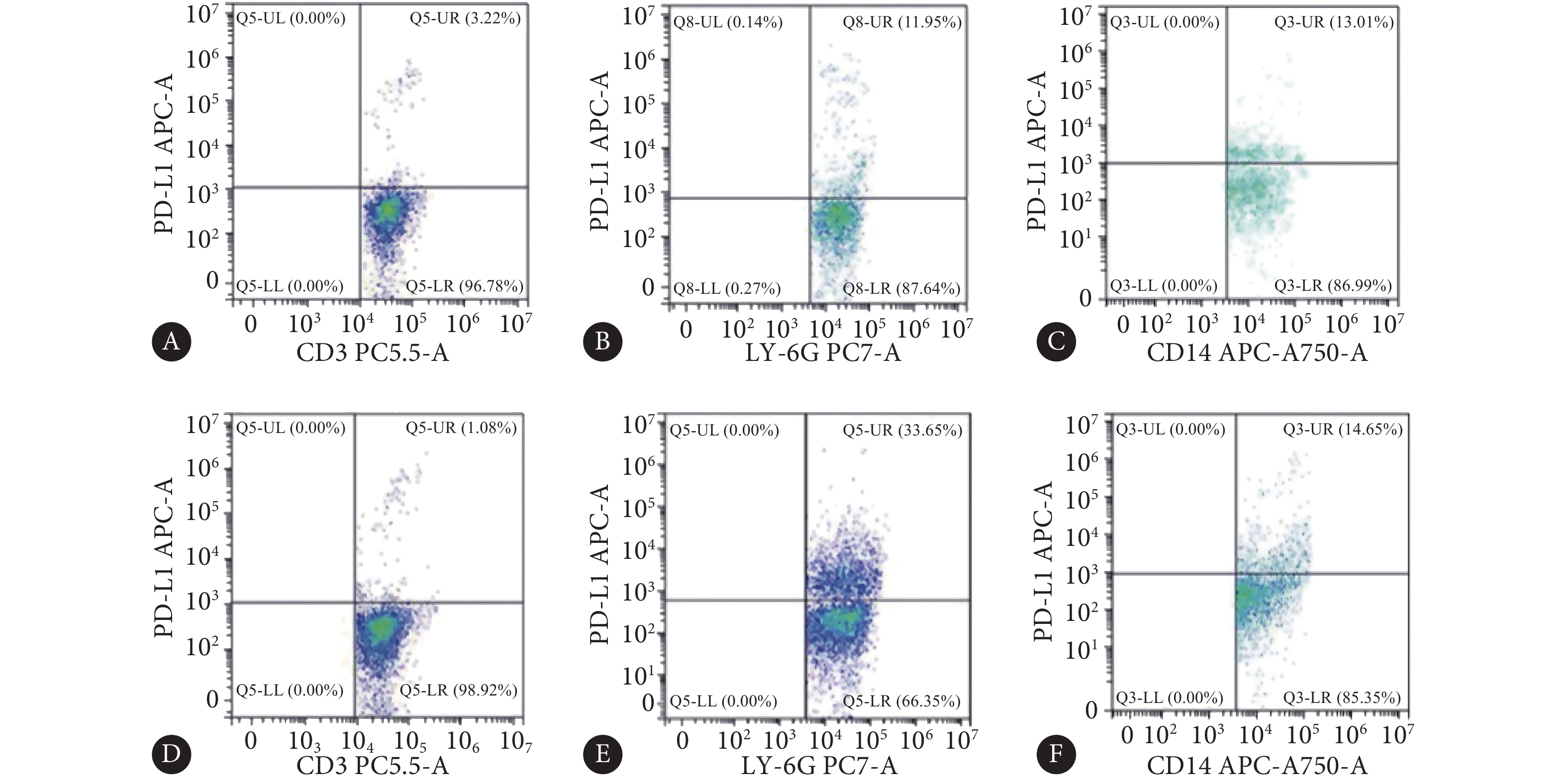

图 4 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群占总白细胞比例Figure 4. Proportion of leukocyte subsets in total leukocytes in the peripheral blood of wild-type miceA: T cells in the control group; B: Neutrophils in the control group; C: Monocytes in the control group; D: T cells in NEC group; E: Neutrophils in NEC group; F: Monocytes in NEC group.对照组小鼠外周血T淋巴细胞、中性粒细胞、单核细胞中PD-L1(+)细胞比例(%)分别为2.46±0.88、13.45±3.04、14.51±3.35;造模组小鼠外周血T淋巴细胞、中性粒细胞、单核细胞中细胞比例(%)分别为2.12±1.09、33.49±3.4、13.67±2.62,其中PD-L1(+)中性粒细胞比例较对照组增加约150%(P<0.05)(图5)。

![]() 图 5 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群PD-L1(+)细胞比例Figure 5. Proportion of PD-L1 (+) cells in the peripheral blood leukocyte subsets of wild-type miceA: PD-L1+ T cells in the control group; B: PD-L1+ neutrophils in the control group; C: PD-L1+ monocytes in the control group; D: PD-L1+ T cells in NEC group; E: PD-L1+ neutrophils in NEC group; F: PD-L1+ monocytes in NEC group.

图 5 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群PD-L1(+)细胞比例Figure 5. Proportion of PD-L1 (+) cells in the peripheral blood leukocyte subsets of wild-type miceA: PD-L1+ T cells in the control group; B: PD-L1+ neutrophils in the control group; C: PD-L1+ monocytes in the control group; D: PD-L1+ T cells in NEC group; E: PD-L1+ neutrophils in NEC group; F: PD-L1+ monocytes in NEC group.2.5 PD-L1基因鼠NEC模型诱导结果

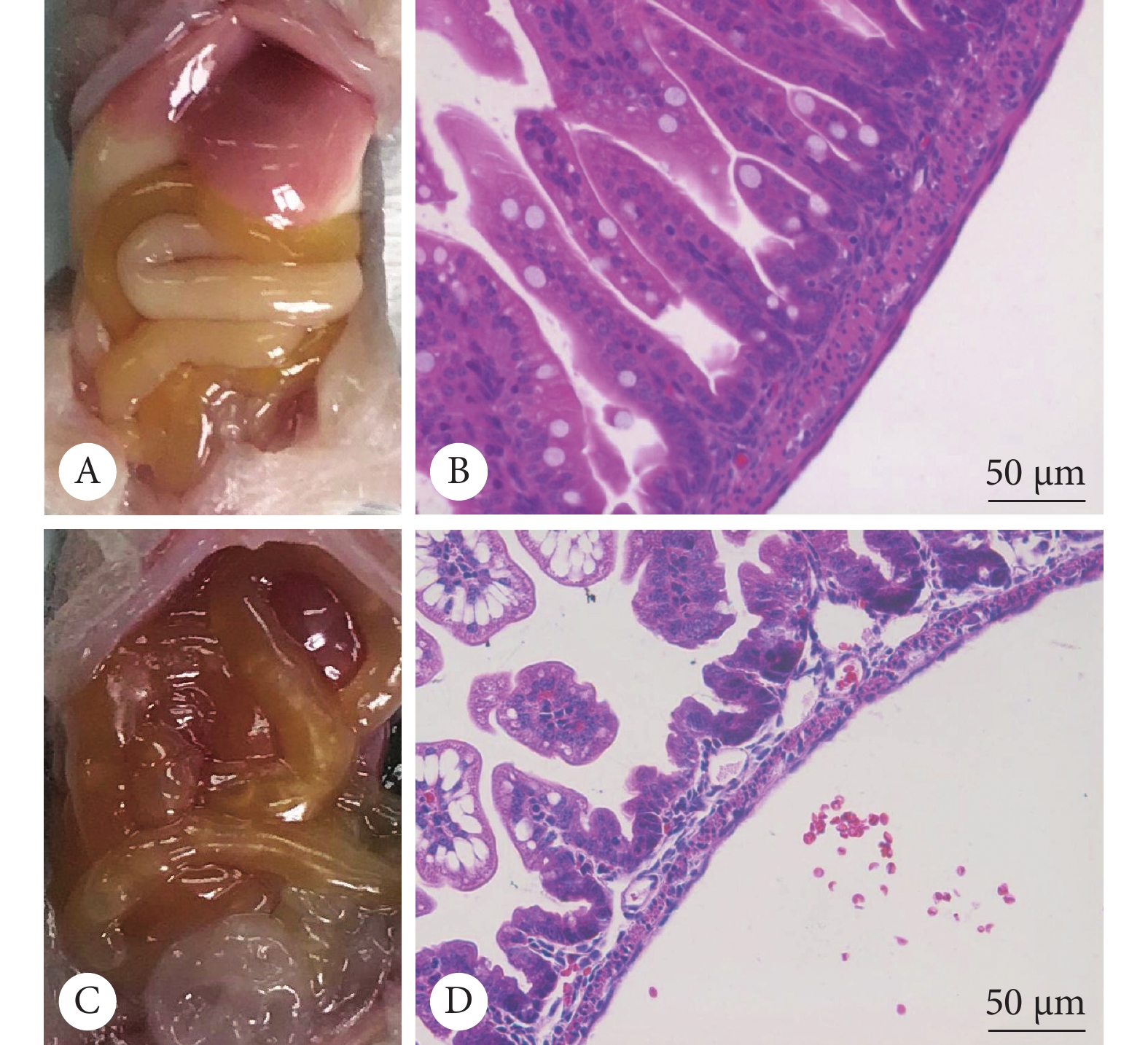

大体病理显示,对照组中两种基因型小鼠肠道形态光滑规整,颜色呈乳白至淡黄,肠壁无充血,肠腔无积气,组内未见明显差别;造模组小鼠肠道颜色较对照组加深变暗,部分肠段充血,部分肠腔积气,PD-L1(−/−)小鼠较PD-L1(+/+)小鼠肠道颜色更深,部分肠段呈紫黑色。HE染色显示,对照组中两种基因型小鼠肠壁各层连接紧密,无水肿、分离,肠绒毛完整,组内未见明显差别;造模组小鼠有不同程度的的黏膜/黏膜下水肿分离,伴肠绒毛脱落,PD-L1(−/−)小鼠较PD-L1(+/+)小鼠肠壁水肿分离更重,肠绒毛脱落缺失的程度更重、范围更大(图6)。

按病理标准评分,对照组PD-L1(+/+)小鼠与PD-L1(−/−)小鼠肠道病理评分分别为0.2±0.16和0.17±0.14,两组间无明显差异(P>0.05);造模组PD-L1(−/−)小鼠和PD-L1(+/+)小鼠肠道病理评分分别为1.97±0.31和2.71±0.23,差异有统计学意义(P<0.01)。造模组PD-L1(+/+)小鼠模型诱导成功率为57%(4/7),造模组PD-L1(−/−)小鼠模型诱导成功率为100%(7/7)。

2.6 PD-L1基因鼠外周血炎症因子表达

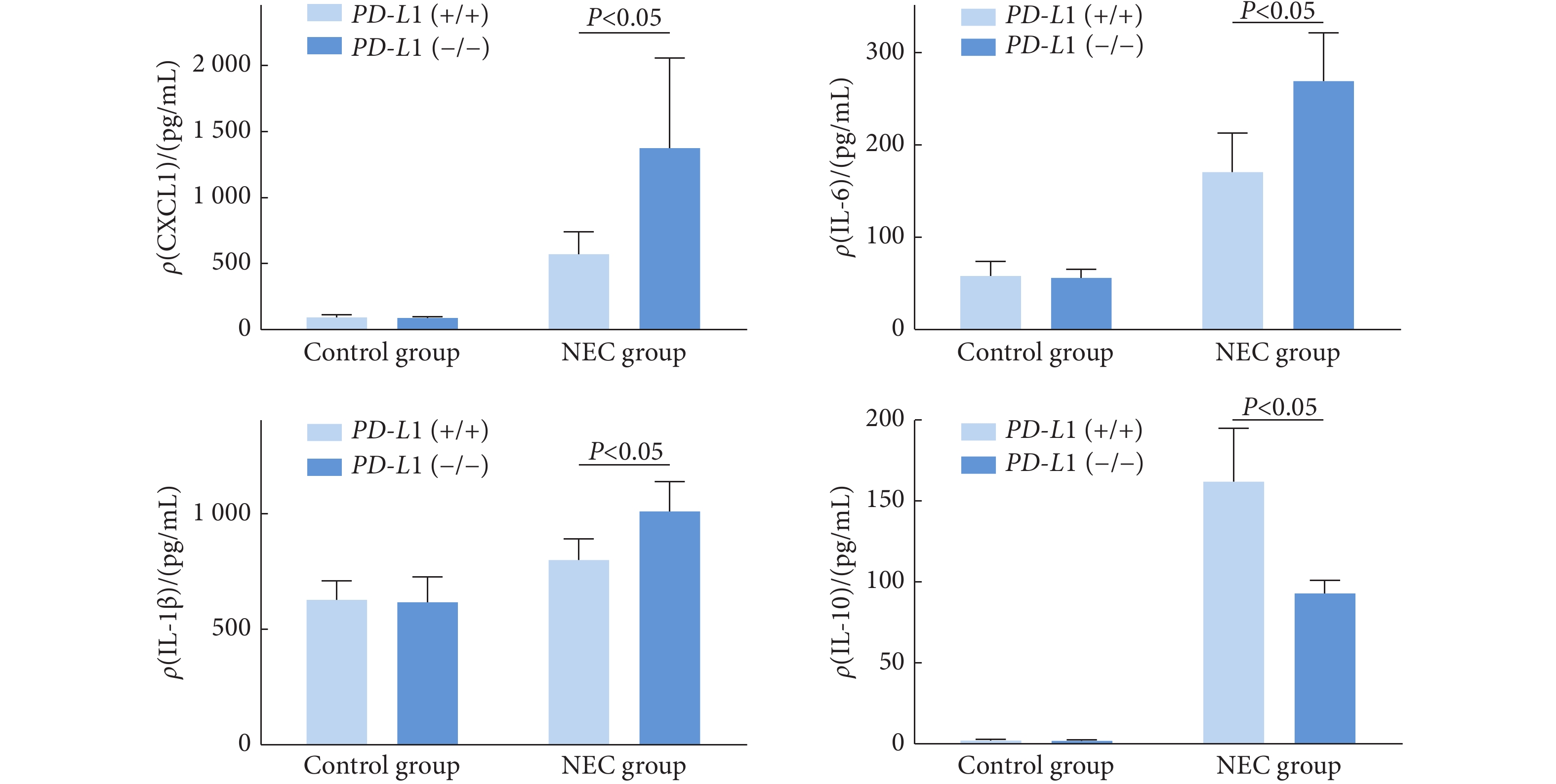

在对照组,PD-L1(−/−)

小鼠与PD-L1(+/+)小鼠的CXCL1、IL-6、IL-1β、IL-10的表达未见明显差异(P>0.05)。在造模组中,相较于PD-L1(+/+)小鼠,PD-L1(−/−)小鼠的CXCL1、IL-6和IL-1β表达分别增加了约160%、70%和26%(P<0.05),IL-10表达下降了约43%(P<0.05)(图7)。 3. 讨论

随着早产儿存活率的提升,NEC的发病率随之增加[4],对NEC的炎症调控机制进行更深入的探究也成为更加迫切的需要。

PD-L1是免疫反应中的负性调节共刺激分子之一,它能诱导活化的T细胞、B细胞凋亡,介导免疫逃逸[18-19]。有文章指出在脓毒症中PD-L1在中性粒细胞中的高表达是脓毒症晚期机体免疫抑制状态形成的重要原因[20],但是目前对于PD-L1在炎症调控中的作用尚无统一的观点,甚至有动物实验研究报道阻断PD-L1通路后,炎症反应减轻[14, 16]。所以对于PD-L1在炎症调控中的作用,尤其是对于NEC,仍需深入探索。

为了探索PD-L1在NEC炎症调控中的作用,首先需要明确PD-L1的表达情况。本研究在NEC小鼠模型中发现PD-L1广泛表达于小鼠炎症细胞和肠上皮细胞,且相较于母乳喂养小鼠,NEC小鼠外周血中性粒细胞及肠道PD-L1表达均有明显增加。而在肠道炎症发生发展中,主要炎症细胞包括局部定居的黏膜相关淋巴细胞以及通过趋化因子从血液募集的白细胞[21]。随后本研究利用PD-L1(+/+)小鼠与PD-L1(−/−)小鼠分别设置对照组和造模组进行分析,发现两种基因型的母乳喂养小鼠的生长情况、肠道形态、炎症水平均无明显差异,而造模组PD-L1(−/−)

小鼠肠道病理改变程度较PD-L1(+/+)小鼠明显加重。同时,造模组PD-L1(−/−)小鼠血清中的CXCL1、IL-6和IL-1β水平较PD-L1(+/+)小鼠分别增加了约160%、70%和26%,IL-10的水平下降超过40%。CXCL1、IL-6和IL-1β都是经典的促炎因子,在炎症进程中常常作为炎症水平的观察指标,包括COVID-19引起的肺炎[22],这些炎症促进因子的上调和炎症抑制因子IL-10[23]表达水平降低共同提示了PD-L1(−/−) 小鼠较PD-L1(+/+)小鼠有着更重的炎症水平,这一变化与肠道病理变化相一致。同时,NEC小鼠外周血白细胞以及PD-L1阳性的白细胞变化均主要发生于中性粒细胞,加之CXCL1这一变化幅度最为明显的炎症因子主要由成纤维细胞、中性粒细胞和上皮细胞产生[24-25],具有强烈的中性粒细胞趋化活性 [26-27],我们推测引起两种基因型小鼠炎症差异的机制可能在于PD-L1对中性粒细胞的调控。 综上所述,本研究发现在小鼠中PD-L1广泛表达于炎症细胞和肠上皮细胞,在接受NEC模型诱导后,PD-L1表达明显增加,而敲除PD-L1

基因使得小鼠肠道病理改变明显加重,炎症因子水平亦明显增加,PD-L1在NEC发病中起着抑制炎症反应的保护作用。但其作用机制是否通过调控中性粒细胞来实现,尚需进一步研究。本研究首次提出PD-L1在NEC发病中的调控作用,并采用了基因敲除鼠进行验证,这或可为NEC的诊断和治疗提供新的转化思路和实验依据。 * * *

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

-

图 2 PD-L1蛋白在野生型小鼠肠道的定位。×400(上排图片放大倍数)

Figure 2. Localization of PD-L1 protein in the intestines of wild-type mice.×400 (magnification of the upper image)

A: The spleen tissue (PD-L1+ control); B: Intestines of the control group; C: Intestines of NEC group. Green represents the PD-L1 protein, red represents the CD45 protein, and blue represents the nucleus.

图 4 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群占总白细胞比例

Figure 4. Proportion of leukocyte subsets in total leukocytes in the peripheral blood of wild-type mice

A: T cells in the control group; B: Neutrophils in the control group; C: Monocytes in the control group; D: T cells in NEC group; E: Neutrophils in NEC group; F: Monocytes in NEC group.

图 5 野生型小鼠外周血白细胞亚群PD-L1(+)细胞比例

Figure 5. Proportion of PD-L1 (+) cells in the peripheral blood leukocyte subsets of wild-type mice

A: PD-L1+ T cells in the control group; B: PD-L1+ neutrophils in the control group; C: PD-L1+ monocytes in the control group; D: PD-L1+ T cells in NEC group; E: PD-L1+ neutrophils in NEC group; F: PD-L1+ monocytes in NEC group.

-

[1] NEU J, WALKER W A. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med,2011,364(3): 255–264. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1005408

[2] HACKAM D J, UPPERMAN J S, GRISHIN A, et al. Disordered enterocyte signaling and intestinal barrier dysfunction in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg,2005,14(1): 49–57. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2004.10.025

[3] NIÑO D F, SODHI C P, HACKAM D J. Necrotizing enterocolitis: New insights into pathogenesis and mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol,2016,13(10): 590–600. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.119

[4] TAM P K H, CHUNG P H Y, PEYER S D S, et al. Advances in paediatric gastroenterology. Lancet,2017,390(10099): 1072–1082. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32284-5

[5] ANAND R J, LEAPHART C L, MOLLEN K P, et al. The role of the intestinal barrier in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Shock,2007,27(2): 124–133. DOI: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239774.02904.65

[6] GRIBAR S C, ANAND R J, SODHI C P, et al. The role of epithelial Toll-like receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. J Leukoc Biol,2008,83(3): 493–498. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.0607358

[7] FROST B L, MODI B P, JAKSIC T, et al. New medical and surgical insights into neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: A review. JAMA Pediatr,2017,171(1): 83–88. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2708

[8] BAZACLIU C, NEU J. Pathophysiology of necrotizing enterocolitis: An update. Curr Pediatr Rev,2019,15(2): 68–87. DOI: 10.2174/1573396314666181102123030

[9] EATON S, REES C M, HALL N J. Current research on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management of necrotizing enterocolitis. Neonatology,2017,111(4): 423–430. DOI: 10.1159/000458462

[10] CHEN Y W, ZHANG J B, GUO G N, et al. Induced B7-H1 expression on human renal tubular epithelial cells by the sublytic terminal complement complex C5b-9. Mol Immunol,2009,46(3): 375–383. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.026

[11] HUTCHINS N A, WANG F, WANG Y, et al. Kupffer cells potentiate liver sinusoidal endothelial cell injury in sepsis by ligating programmed cell death ligand-1. J Leukoc Biol,2013,94(5): 963–970. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.0113051

[12] PAYIL N K, GUO Y, LUAN L M, et al. Targeting immune cell checkpoints during spesis. Int J Mol Sci,2017,18(11): 2413. DOI: 10.3390/ijms18112413

[13] PATERA A C, DREWRY A M, CHANG K, et al. Frontline science: Defects in immune function in patients with sepsis are associated with PD-1 or PD-L1 expression and can be restored by antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1. J Leukoc Biol,2016,100(6): 1239–1254. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.4HI0616-255R

[14] WU Y, CHUNG C S, CHEN Y, et al. A novel role for programmed cell death receptor ligand-1 in sepsis-induced intestinal dysfunction. Mol Med,2017,22: 830–840. DOI: 10.2119/molmed.2016.00150

[15] MARINA C, ELLEN J B, IRINA V P. Role of PD-L1 in gut mucosa tolerance and chronic inflammation. Int J Mol Sci,2020,21(23): 9165. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21239165

[16] KANAI T, TOTSUKA T, URAUSHIHARA K, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 suppresses the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol,2003,171(8): 4156–4163. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4156

[17] NADLER E P, DICKINSON E, KNISELY A, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-12 in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. J Surg Res,2000,92(1): 71–77. DOI: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5877

[18] DONG H, ZHU G, TAMADA K, et al. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med,1999,5(12): 1365–1369. DOI: 10.1038/70932

[19] SHEPPARD K A, FITZ L J, LEE J M, et al. PD-1 inhibits T-cell receptor induced phosphorylation of the ZAP70/CD3zeta signalosome and downstream signaling to PKCtheta. FEBS Lett,2004,574(1/2/3): 37–41. DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.083

[20] LANGEREIS J D, PICKKERS P, KLEIJN S D, et al. Spleen-derived IFN-g induces generation of PD-L1+-suppressive neutrophils during endotoxemia. J Leukoc Biol,2017,102(6): 1401–1409. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.3A0217-051RR

[21] MARKEL T A, CRISOSTOMO P R, WAIRIUKO G M, et al. Cytokines in necrotizing enterocolitis. Shock,2006,25(4): 329–337. DOI: 10.1097/01.shk.0000192126.33823.87

[22] GONG J, DONG H, XIA Q S, et al. Correlation analysis between disease severity and inflammation-related parameters in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis,2020,20(1): 963. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-020-05681-5

[23] ABDERRAZAK A, SYROVETS T, COUCHIE D, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: From a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol,2015,4: 296–307. DOI: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.008

[24] LIDA N, GROTENDORST G R. Cloning and sequencing of a new grotranscriptfrom activated human monocytes: Expression in leukocytes and wound tissue. Mol Cell Biol,1990,10(10): 5596–5599. DOI: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5596-5599.1990

[25] SUSEK KH, KARVOUNI M, ALICI E, et al. The role of CXC chemokine receptors 1–4 on immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 2159[2021-04-05]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02159.

[26] VRIES M H M, WAGENAAR A, VERBRUGGEN S E L, et al. CXCL1 promotes arteriogenesis through enhanced monocyte recruitment into the peri-collateral space. Angiogenesis,2015,18(2): 163–171. DOI: 10.1007/s10456-014-9454-1

[27] HAGHNEGAHDAR H, DU J, STRIETER R M, et al. The tumorigenic and angiogenic effects of MGSA/GRO proteins in melanoma. J Leukoc Biol,2000,67(1): 53–62. DOI: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.53

首页

首页

下载:

下载: