Exploring the Causal Relationship Between Circulating Immune Cells and Autoimmune Hepatitis Through Mendelian Randomization Analysis

-

摘要:目的

通过两样本孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization, MR)方法,阐明特定免疫细胞与自身免疫性肝炎(autoimmune hepatitis, AIH)之间的因果关系。

方法利用了大型公共全基因组关联研究(Genome-Wide Association Study, GWAS)数据库,进行了双向MR分析,以逆方差加权法(Inverse variance weighted,IVW)为主要方法,评估731种免疫细胞表型与AIH之间的关系。通过Benjamini-Hochberg校正控制错误发现率(false discovery rate, FDR),并进行了多效性与异质性检验,同时采用留一法敏感性分析以进一步验证结果的稳健性。

结果在显著性水平为0.20的条件下,发现CD28−CD8+调节性T细胞绝对计数〔IVW:比值比(odds ratio, OR)=1.486,95%置信区间(confidence interval, CI):1.189~1.859,P<0.001;PFDR=0.185〕、分泌CD39+的调节性T细胞上的CD28水平(IVW:OR=1.194,95%CI:1.074~1.328,P=0.001;PFDR=0.185)和单核髓源性抑制细胞上的CD45水平(IVW:OR=1.243,95%CI:1.108~1.394,P<0.001;PFDR=0.143)与AIH风险增加存在因果关系,而CD14+CD16+单核细胞上的程序死亡-配体1水平(IVW:OR=0.849,95%CI:0.771~0.935,P<0.001;PFDR=0.185)与AIH风险降低存在因果关系。

结论本研究确定了四个与AIH相关的免疫细胞表型,需进一步研究验证这些发现并探索新的治疗途径。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo elucidate the causal relationship between specific immune cells and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) using a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) approach.

MethodsA bidirectional MR analysis was conducted using data from large publicly accessible Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) databases. The inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was employed as the primary method to evaluate the relationship between 731 immune cell traits and AIH. The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Additionally, pleiotropy and heterogeneity tests were performed, and a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to further validate the robustness of the results.

ResultsAt a significance level of 0.20, it was found that the absolute count of CD28−CD8+ regulatory T-cells (IVW: odds ratio [OR] = 1.486; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.189-1.859; P < 0.001; PFDR = 0.185), the level of CD28 on CD39+ secreting regulatory T-cells (IVW: OR = 1.194; 95% CI, 1.074-1.328; P = 0.001; PFDR = 0.185), and the level of CD45 on mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (IVW: OR = 1.243; 95% CI, 1.108-1.394; P < 0.001; PFDR = 0.143) were associated with an increased risk of AIH. The level of programmed death-ligand 1 on CD14+CD16+ monocytes (IVW: OR = 0.849; 95% CI, 0.771-0.935; P < 0.001; PFDR = 0.185) was associated with a reduced risk of AIH.

ConclusionFour immune cell phenotypes associated with AIH risk are identified. Further investigation is needed to validate these findings and explore new therapeutic avenues.

-

Keywords:

- Autoimmune hepatitis /

- Mendelian randomization /

- Immune cells

-

自身免疫性肝炎(autoimmune hepatitis, AIH)是一种由免疫系统异常引发的持续性肝内炎症,导致肝脏的非化脓性损伤。根据以往的流行病学研究,不同地区的AIH年发病率不同,AIH为每10万人0.4~2.39例,相应的患病率为每10万人4.8~42.9例,尽管AIH的患病率较低,但它造成了不成比例的高临床负担[1]。

AIH的发病机制尚不明确。与其他自身免疫性疾病不同,因AIH发病率较低,研究较少,其潜在机制尚未充分探明。大多数AIH患者起病隐匿,早期仅表现为血清中以IgG为主的免疫球蛋白水平升高,90%的患者出现抗核抗体(antinuclear antibody, ANA)阳性[2]。免疫耐受的紊乱在AIH的发病中起关键作用[3],调节性T细胞(regulatory T-cells, Treg)通过与其他免疫细胞的相互作用实现免疫调节[4]。研究表明,AIH患者的Treg不仅数量减少,功能也受损,包括对白细胞介素-2(interleukin-2, IL-2)反应缺陷及低水平的IL-10产生[5]。在肝脏中,IL-6可刺激多种急性期蛋白的合成,从而促进急性炎症反应。相比于普通人群,携带IL-6基因突变的人群发生AIH的风险显著增加[6]。AIH的治疗主要依赖免疫抑制,类固醇是一线药物,但大约10%~20%的患者对一线治疗反应不佳或因严重副作用停止治疗。越来越多的研究关注更精细化的免疫调节对AIH的治疗,全面研究免疫细胞与AIH之间的关系可能为AIH治疗提供新方向[7]。

孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization, MR)作为一种流行病学分析方法,利用孟德尔遗传原理推断因果关系,通过遗传变异来阐明暴露与结局之间的因果关系[8]。尽管随机对照试验在循证医学中被认为是最高级别证据,但由于可行性差、成本高以及伦理问题,可能并非最佳选择。传统观察性研究由于选择偏倚、混杂因素或反向因果关系等原因,难以准确建立因果关系[9]。相比之下,MR可以减少这些偏倚。本研究通过全面的两样本MR分析,探究多种免疫细胞与AIH之间的因果关系。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 研究设计与伦理批准

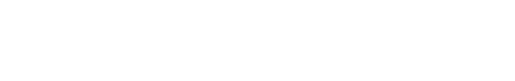

本研究采用了两样本MR方法来探索731个免疫细胞表型与AIH之间的因果关系。单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP)被用作工具变量,并遵循三个基本假设:①工具变量必须与暴露直接相关;②工具变量必须独立于混杂因素;③工具变量仅通过暴露影响结局[10]。本研究的详细步骤见图1。本研究使用已发表的公共全基因组关联研究(Genome-Wide Association Study, GWAS)数据已由相应的伦理委员会批准,因此无须为本研究额外申请伦理审批。

1.2 免疫细胞数据来源

免疫细胞GWAS数据来源于IEU OPEN GWAS(访问编号从ebi-a-GCST90001391到ebi-a-GCST90002121)(https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/)。原始研究基于欧洲血统的来自撒丁岛的3 757人队列,报告了大约

2200 万个SNP,涉及731个免疫细胞表型。基于流式细胞术染色,731个免疫细胞表型被分类为七个组(panel):调节性T细胞、树突状细胞、B细胞、髓样细胞、单核细胞、T细胞成熟阶段和TBNK(T细胞、B细胞、自然杀伤细胞)。表型类型包括绝对细胞计数、相对细胞计数、中位荧光强度和形态参数[11]。1.3 AIH数据来源

AIH(GCST90018785)的汇总统计数据来自GWAS Catalog中的相应研究(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/)。数据集包括欧洲血统来自英国和芬兰的821例病例和484 413例对照[12]。

1.4 工具变量筛选

参考以往的研究,本研究从免疫细胞表型中筛选SNP以1×10−5为显著性阈值[13-14],而筛选AIH中SNP的显著性阈值设定为5×10−6[15]。为保证SNP的独立性,本研究进行了去连锁不平衡,SNP之间的距离阈值为

10000 kb,并且r2<0.001。每个SNP的F统计量计算公式为F=beta2/SE2,其中beta表示对暴露的影响大小,SE表示其标准误,如果F小于10,则表明该SNP为弱工具变量[16],并将该SNP从后续分析中移除。在每次数据协调过程中,次要等位基因频率在0.42到0.58范围内的回文SNP会被定义为模糊SNP,并被自动移除[17]。为了避免直接关联,显示出对结局显著性大于对暴露的显著性(Poutcome<Pexposure)的SNP被排除[18]。最终用于后续MR分析的SNP详见附表1,所有附表见网络资源附件。1.5 统计学方法

逆方差加权法(inverse variance weighted, IVW)被用作本研究中探索免疫细胞表型与AIH之间因果关系的主要分析方法[19],MR-Egger回归法、加权中位数法(weight median)、简单众数法(simple mode)和加权众数法(weighted mode)被用作补充方法。为了降低错误发现率(false discovery rate, FDR),本研究采用了Benjamini-Hochberg校正方法[20],并将显著性阈值设定为0.20[21-22]。为了避免水平多效性带来的潜在偏倚,进行了MR-Egger截距分析和MR-PRESSO全局测试[23],并采用Cochran's Q检验来检测选定工具变量的异质性[24]。此外,本研究进行了留一法敏感性分析,以评估单个SNP对总体因果效应的影响并排除离群值[25]。

数据分析和绘图是在R软件(版本4.4.0)中进行的,R软件包主要包括“TwoSampleMR”(版本0.6.2)和“MRPRESSO”(版本1.0)。

2. 结果

2.1 免疫细胞对AIH的因果效应

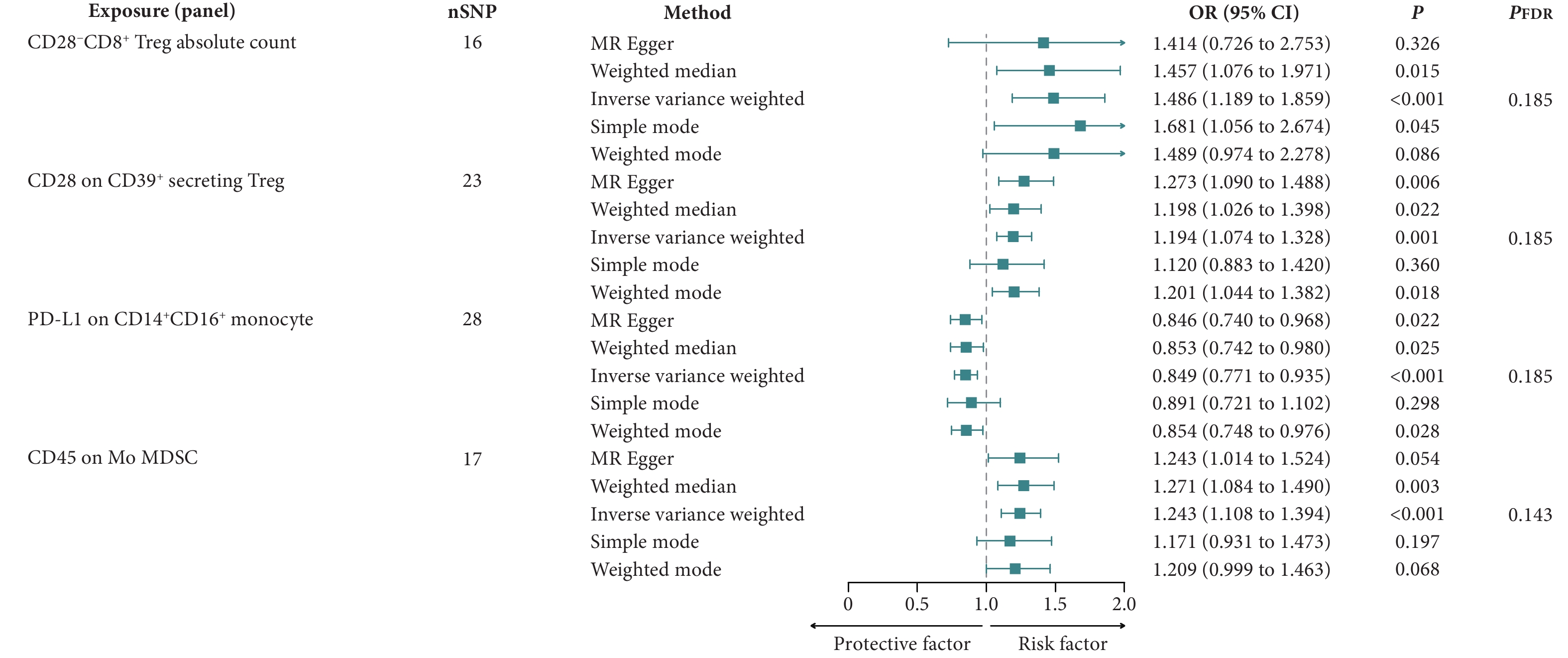

本研究采用两样本MR分析探索免疫细胞与AIH的因果关系,并以IVW方法作为主要的分析方法。应用FDR校正后,在0.05的显著性水平上,未发现任何免疫细胞表型具有统计学意义。在0.20的显著性水平上,发现有四个表型对AIH有因果效应。其中,CD28−CD8+ Treg绝对计数、分泌CD39+的Treg上的CD28水平和单核髓源性抑制细胞(mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Mo MDSC)上的CD45水平与AIH风险增加存在因果关系,而CD14+CD16+单核细胞上的程序死亡-配体1(programmed death-ligand 1, PD-L1)水平与AIH风险降低存在因果关系(图2、图3)。以IVW方法评估CD28−CD8+ Treg绝对计数对AIH的比值比(odds ratio, OR)为1.486〔95%置信区间(confidence interval, CI)为1.189~1.859,P<0.001;PFDR=0.185〕,其他两种方法〔加权中位数法(OR=1.457,95%CI:1.076~1.971,P=0.015)和简单众数法(OR=1.681,95%CI:1.056~2.674,P=0.045)〕的结果类似。以IVW方法评估分泌CD39+的Treg上的CD28,OR为1.194(95%CI:1.074~1.328,P=0.001;PFDR=0.185),其他三种方法〔MR-Egger(OR=1.273,95%CI:1.090~1.488,P=0.006)、加权中位数法(OR=1.198,95%CI:1.026~1.398,P=0.022)和加权众数法(OR=1.201,95%CI:1.044~1.382,P=0.018)〕的结果类似。CD14+CD16+单核细胞上的PD-L1的IVW方法结果是OR为0.849(95%CI:0.771~0.935,P<0.001;PFDR=0.185),其他三种方法〔MR-Egger(OR=0.846,95%CI:0.740~0.968,P=0.022)、加权中位数法(OR=0.853,95%CI:0.742~0.980,P=0.025)和加权众数法(OR=0.854,95%CI:0.748~0.976,P=0.028)〕的结果类似。以IVW方法评估单核髓源性抑制细胞上的CD45,OR为1.243(95%CI:1.108~1.394,P<0.001;PFDR=0.143),加权中位数法的结果类似(OR=1.271,95%CI:1.084~1.490,P=0.003)。

![]() 图 2 森林图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的因果效应Figure 2. The forest plot shows the effects of immune cells on AIHnSNP: the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; FDR: false discovery rate; Treg: regulatory T-cells; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; Mo MDSC: mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

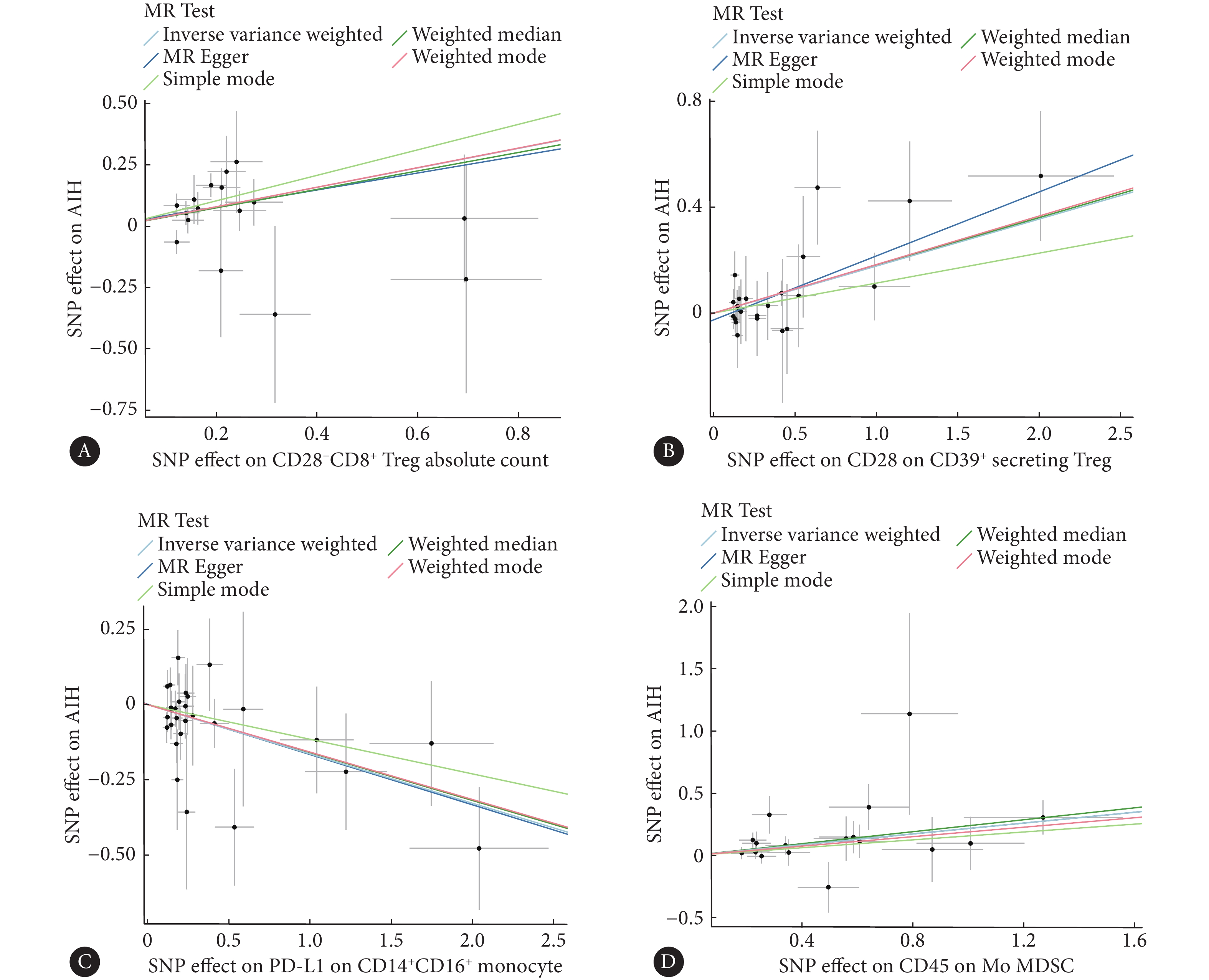

图 2 森林图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的因果效应Figure 2. The forest plot shows the effects of immune cells on AIHnSNP: the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; FDR: false discovery rate; Treg: regulatory T-cells; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; Mo MDSC: mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells.![]() 图 3 散点图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响Figure 3. The scatter plot shows the effect of immune cells on AIHAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. A, The ffect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.

图 3 散点图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响Figure 3. The scatter plot shows the effect of immune cells on AIHAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. A, The ffect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.2.2 敏感性分析

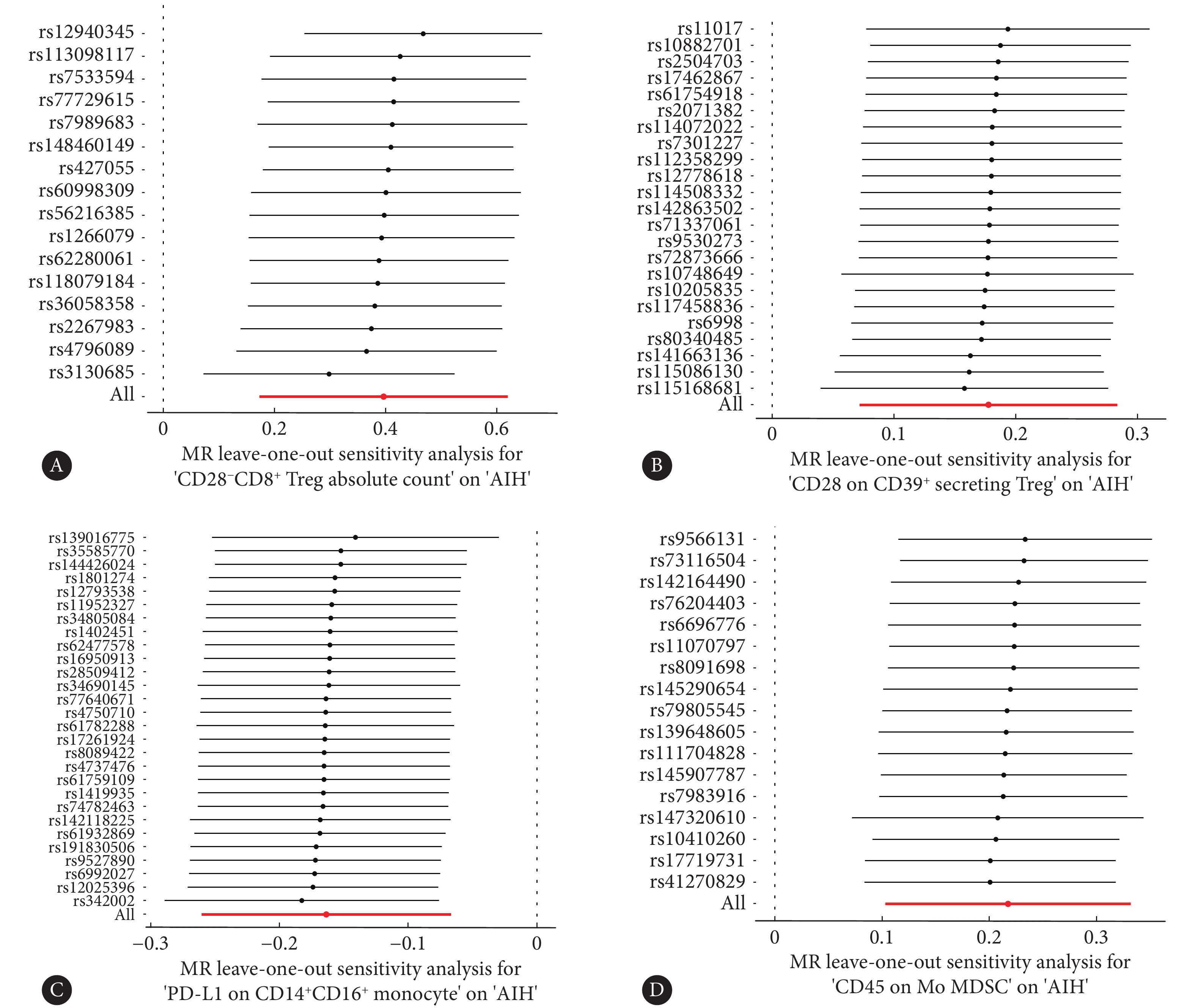

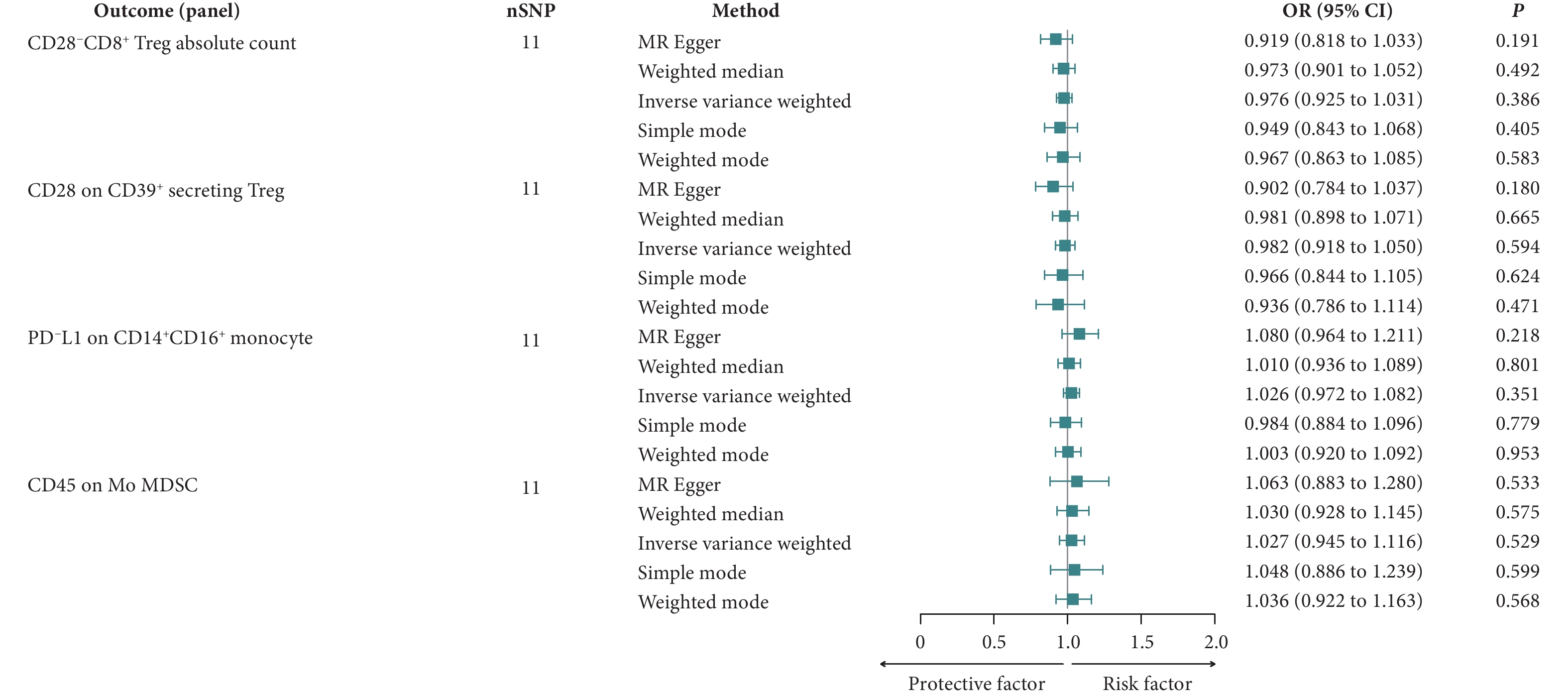

敏感性分析中的MR-Egger截距分析显示,这四个免疫表型没有显著的水平多效性(P>0.05),这一结果得到了MR-PRESSO全局测试的进一步验证(P>0.05)(表1)。Cochran's Q检验的P值超过0.05,表明与AIH相关的这些SNP中不存在异质性(表2)。在留一法敏感性分析过程中,将每个SNP依次排除后,计算剩余SNP对总体因果关系的影响,未发现任何单个SNP主导总体因果效应(图4)。采用反向MR来评估AIH对免疫细胞的因果效应,结果显示P值均高于0.05,意味着AIH对这四个免疫细胞表型没有显著影响(图5)。

表 1 免疫细胞与AIH的多效性检验Table 1. The pleiotropy test for immune cells and AIHExposure P MR-Egger-

interceptMR-PRESSO

global testCD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count 0.877 0.307 CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg 0.283 0.863 PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte 0.944 0.665 CD45 on Mo MDSC > 0.999 0.728 All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. 表 2 免疫细胞与AIH的异质性检验Table 2. The heterogeneity test for immune cells and AIHExposure Method P (Cochran's Q test) CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count MR-Egger 0.225 IVW 0.282 CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg MR-Egger 0.957 IVW 0.946 PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte MR-Egger 0.551 IVW 0.606 CD45 on Mo MDSC MR-Egger 0.552 IVW 0.625 All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. ![]() 图 4 留一法敏感性分析图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响Figure 4. The leave-one-out plot of sensitivity analysis shows the effect of immune cells on AIHAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. Each point represents the causal effect estimated by IVW after removing a single SNP. A, The effect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.

图 4 留一法敏感性分析图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响Figure 4. The leave-one-out plot of sensitivity analysis shows the effect of immune cells on AIHAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. Each point represents the causal effect estimated by IVW after removing a single SNP. A, The effect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.![]() 图 5 反向MR结果展示了AIH对免疫细胞的影响Figure 5. The reverse MR results of the effects of AIH on immune cellsAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2.

图 5 反向MR结果展示了AIH对免疫细胞的影响Figure 5. The reverse MR results of the effects of AIH on immune cellsAll abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2.3. 讨论

基于大型的公共GWAS数据,本研究探索了731个免疫细胞表型与AIH之间的因果关系。经过严格的筛选和全面的多效性、异质性检测和留一法敏感性分析,确定了四个与AIH相关的免疫细胞表型。

本研究表明,CD28−CD8+ Treg绝对计数与AIH风险增加存在因果关系。Treg通过抑制免疫应答和炎症反应,在维持机体免疫稳态方面发挥关键作用[26]。Treg功能异常已被证实与自身免疫性疾病及肿瘤的发病机制密切相关[27-28]。已有研究发现,在多种自身免疫性疾病中,CD28−CD8+ Treg的比例发生了显著变化[29]。然而,先前研究并未在健康个体与AIH患者之间观察到CD28−CD8+ Treg的增加,可能是由于人群异质性和样本量有限[30]。在类风湿性关节炎患者中,外周血中CD28−CD8+ Treg增加,且在仅用甲氨蝶呤治疗的患者中,Treg的免疫调节功能是有缺陷的,这一现象可以通过肿瘤坏死因子抑制剂部分缓解[31]。系统性硬化患者中,循环中和皮肤病变部位的CD28−CD8+ T细胞的比例显著增加,这些细胞因高表达的颗粒酶B和穿孔蛋白而显示出潜在的细胞毒性,并高表达促纤维化的IL-13和促炎的干扰素-γ(interferon-γ, INF-γ)[32]。有研究表明,AIH患者的Treg对CD8+和CD4+效应T细胞增殖的抑制作用减弱,且这些患者的Treg表现出升高的INF-γ表达水平和类似Th1细胞的细胞因子谱[3, 33],因此,推测AIH患者中CD28−CD8+ Treg的免疫调节功能可能受损。

研究还发现,分泌CD39+的Treg上的CD28水平与AIH风险增加存在因果关系。CD28作为共刺激受体,与T细胞受体共同调节T细胞的增殖和功能[34]。虽然CD28在维持Treg稳态和免疫调节功能中发挥关键作用,但也有文献表明,CD28在某些情况下可以抑制Treg的免疫调节功能并激活效应T细胞[35],这暗示CD28在不同类型的Treg或不同微环境中可能具有不同的功能。腺苷能信号通路在免疫调节中起重要作用,Treg通过表达膜蛋白CD39和CD73参与其中。CD39将胞外的三磷酸核苷(adenosine triphosphate, ATP)和二磷酸核苷(adenosine diphosphate, ADP)转化为单磷酸腺苷(adenosine monophosphate, AMP),随后由CD73转化为腺苷,腺苷可以与效应T细胞的A2A受体结合,从而抑制T细胞活性[36]。CD28的刺激可以减少CD73的表达及腺苷的产生[37]。在AIH患者中,CD39+ Treg的比例显著下降,伴随着ATP/ADP水解能力的降低[38]。综上所述可以推测AIH患者中CD28可能通过抑制CD39+的Treg中腺苷能信号通路来削弱Treg的免疫调节功能,进而增加了AIH的发病风险。CD28在AIH中发挥的具体作用尚不明确,需结合不同的Treg亚群进一步研究。

本研究发现CD14+CD16+单核细胞上的PD-L1水平与AIH风险降低存在因果关系。CD14+CD16+单核细胞因高度表达人类白细胞抗原-DR、趋化因子受体5、CD80、CD86及肿瘤坏死因子受体1而具有抗原呈递和促炎作用[39],然而,与CD14−CD16+单核细胞和CD14+CD16−单核细胞相比,CD14+CD16+单核细胞显示出更高的IL-10表达,表明其也可能介导了抗炎反应[40]。PD-L1不仅表达于细胞膜上,还会被释放到细胞外间隙。PD-1是PD-L1的受体,它在各种免疫细胞中表达,PD-1通路的失调是多种自身免疫病发生的一个促进因素[41]。PD-L1可以抑制CD8+ T细胞的增殖及其细胞毒性作用,同时有助于促进和维持Treg细胞功能[42-43]。有报道称,高表达PD-L1的间充质干细胞(PD-L1high mesenchymal stem cells, PD-L1high MSCs)在促进Treg增殖这一方面比低表达PD-L1的MSCs更有效。PD-L1high MSCs产生更高水平的IL-4和IL-10,而IL-6和IL-8的表达则下调,表明这些细胞具有更强的抗炎能力。在AIH实验模型中,PD-L1high MSCs的注射更大程度地抑制了肝细胞凋亡和炎症浸润[44]。综上所述可以推测,CD14+CD16+单核细胞分泌的PD-L1通过抑制炎症反应和细胞毒性作用来保护肝细胞,这可能成为AIH治疗的潜在靶点。

本研究还发现,单核髓源性抑制细胞上的CD45水平与AIH风险降低存在因果关系。髓源性抑制细胞(mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells,MDSC)是一类具有强大免疫抑制能力的中性粒细胞和单核细胞,它分为两大类:多形核MDSC和单核MDSC。多形核MDSC和单核MDSC的一个共同特征是转录激活蛋白3(signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, STAT3)的表达上调,MDSC最初在肿瘤中被鉴定出,并越来越广泛地被认识到在许多自身免疫疾病中发挥作用。MDSC通过分泌各种抗炎因子,包括 PD-L1、CD40、IL-10 和转化生长因子-β[45-46],来减轻炎症反应。研究表明,MDSC在AIH实验模型中发挥治疗作用,它们的增殖可以降低疾病活动度[47-48]。目前,CD45在自身免疫疾病中对MDSC的作用尚未被研究。然而,先前的研究表明,肿瘤相关MDSC上CD45的激活降低了信号转导及STAT3活性[49],STAT3在MDSC的增殖和免疫抑制中起调节作用[50]。因此,可以提出假设,CD45通过降低STAT3活性来调节MDSC的抑制功能,从而影响AIH的发病。然而,CD45是如何影响AIH中MDSC的确切机制需要进一步研究。

本研究的两样本MR分析利用了最大的AIH数据库,增强了统计效能,并采用多种分析方法探讨特定免疫细胞与AIH之间的因果关系,使用严格的筛选标准排除异质性和水平多效性。然而,本研究存在一定的局限性。首先,应用了相对宽松的显著性阈值,可能增加错误发现率。其次,由于AIH发病率存在性别异质性且缺乏具体个体水平数据,本研究无法进一步分析特定人群。第三,研究结果均来自欧洲队列,但暴露和结局的队列来自欧洲不同区域,无法排除区域间人群异质性带来的偏倚,且仅使用欧洲队列限制了结果对其他种族群体的外推性。最后,本研究仅关注血液中的免疫细胞表型,未能讨论肝脏中免疫细胞的变化。

* * *

作者贡献声明 冷松负责论文构思、数据审编、正式分析和初稿写作,王克芬负责正式分析和初稿写作,石毓君负责审读与编辑写作,邓成负责经费获取、监督指导和审读与编辑写作。所有作者已经同意将文章提交给本刊,且对将要发表的版本进行最终定稿,并同意对工作的所有方面负责。

Author Contribution LENG Song is responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and writing--original draft. WANG Kefen is responsible for formal analysis and writing--original draft. SHI Yujun is responsible for writing--review and editing. DENG Cheng is responsible for funding acquisition, supervision, and writing--review and editing. All authors consented to the submission of the article to the Journal. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

利益冲突 本文作者邓成是本刊编委会青年编委。该文在编辑评审过程中所有流程严格按照期刊政策进行,且未经其本人经手处理。除此之外,所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

Declaration of Conflicting Interests DENG Cheng is a member of the Junior Editorial Board of the journal. All processes involved in the editing and reviewing of this article were carried out in strict compliance with the journal's policies and there was no inappropriate personal involvement by the author. Other than this, all authors declare no competing interests.

-

图 2 森林图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的因果效应

Figure 2. The forest plot shows the effects of immune cells on AIH

nSNP: the number of single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; FDR: false discovery rate; Treg: regulatory T-cells; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; Mo MDSC: mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

图 3 散点图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响

Figure 3. The scatter plot shows the effect of immune cells on AIH

All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. A, The ffect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.

图 4 留一法敏感性分析图展示了免疫细胞对AIH的影响

Figure 4. The leave-one-out plot of sensitivity analysis shows the effect of immune cells on AIH

All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. Each point represents the causal effect estimated by IVW after removing a single SNP. A, The effect of CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count on AIH; B, the effect of CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg on AIH; C, the effect of PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte on AIH; D, the effect of CD45 on Mo MDSC on AIH.

图 5 反向MR结果展示了AIH对免疫细胞的影响

Figure 5. The reverse MR results of the effects of AIH on immune cells

All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2.

表 1 免疫细胞与AIH的多效性检验

Table 1 The pleiotropy test for immune cells and AIH

Exposure P MR-Egger-

interceptMR-PRESSO

global testCD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count 0.877 0.307 CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg 0.283 0.863 PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte 0.944 0.665 CD45 on Mo MDSC > 0.999 0.728 All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. 表 2 免疫细胞与AIH的异质性检验

Table 2 The heterogeneity test for immune cells and AIH

Exposure Method P (Cochran's Q test) CD28−CD8+ Treg absolute count MR-Egger 0.225 IVW 0.282 CD28 on CD39+ secreting Treg MR-Egger 0.957 IVW 0.946 PD-L1 on CD14+CD16+ monocyte MR-Egger 0.551 IVW 0.606 CD45 on Mo MDSC MR-Egger 0.552 IVW 0.625 All abbreviations are explained in the note to Fig 2. -

[1] TRIVEDI P J, HIRSCHFIELD G M. Recent advances in clinical practice: epidemiology of autoimmune liver diseases. Gut, 2021, 70(10): 1989-2003. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322362.

[2] 田爱平, 李琼, 毛永武, 等. ANA阳性的AIH-PBC重叠综合征与单纯AIH患者抗体特征比较及激素应答影响因素分析. 兰州大学学报(医学版), 2023, 49(5): 41-46. doi: 10.13885/j.issn.1000-2812.2023.05.006. TIAN A P, LI Q, MAO Y W, et al. Comparison of antibody characteristics and hormone response in ANA-positive AIH-PBC overlap syndrome and patients with AIH alone analysis of influencing factors. J Lanzhou Univ (Med Sci), 2023, 49(5): 41-46. doi: 10.13885/j.issn.1000-2812.2023.05.006.

[3] TERZIROLI BERETTA-PICCOLI B, MIELI-VERGANI G, VERGANI D. Autoimmmune hepatitis. Cell Mol Immunol, 2021, 19(2): 158-176. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00768-8.

[4] LONGHI M S, MIELI-VERGANI G, VERGANI D. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis: an updated overview. J Autoimmun, 2021, 119: 102619. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102619.

[5] LIBERAL R, GRANT C R, HOLDER B S, et al. In autoimmune hepatitis type 1 or the autoimmune hepatitis-sclerosing cholangitis variant defective regulatory T-cell responsiveness to IL-2 results in low IL-10 production and impaired suppression. Hepatology, 2015, 62(3): 863-75. doi: 10.1002/hep.27884.

[6] 程新红, 王浩嘉, 王勇, 等. 基于网络药理学及分子对接探究茵陈蒿汤治疗自身免疫性肝炎的作用机制. 兰州大学学报(医学版), 2023, 49(8): 6-15. doi: 10.13885/j.issn.1000-2812.2023.08.002. CHENG X H, WANG H J, WANG Y, et al. Mechanism of Yinchenhao decoction in treating autoimmune hepatitis based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. J Lanzhou Univ (Med Sci), 2023, 49(8): 6-15. doi: 10.13885/j.issn.1000-2812.2023.08.002.

[7] MURATORI L, LOHSE A W, LENZI M. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. BMJ, 2023, 380: e070201. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070201.

[8] BOWDEN J, HOLMES M V. Meta-analysis and mendelian randomization: a review. Res Synth Methods, 2019, 10(4): 486-496. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1346.

[9] SEKULA P, DEL GRECO M F, PATTARO C, et al. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016, 27(11): 3253-3265. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098.

[10] EMDIN C A, KHERA A V, KATHIRESAN S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA, 2017, 318(19): 1925-1926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17219.

[11] ORRU V, STERI M, SIDORE C, et al. Complex genetic signatures in immune cells underlie autoimmunity and inform therapy. Nat Genet, 2020, 52(10): 1036-1045. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0684-4.

[12] SAKAUE S, KANAI M, TANIGAWA Y, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet, 2021, 53(10): 1415-1424. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00931-x.

[13] FEI Y, YU H, WU Y, et al. The causal relationship between immune cells and ankylosing spondylitis: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Arthritis Res Ther, 2024, 26(1): 24. doi: 10.1186/s13075-024-03266-0.

[14] XU Z, LI R, WANG L, et al. Pathogenic role of different phenotypes of immune cells in airway allergic diseases: a study based on Mendelian randomization. Front Immunol, 2024, 15: 1349470. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1349470.

[15] WU W, TONG H M, LI Y S, et al. Rosacea and autoimmune liver diseases: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Arch Dermatol Res, 2024, 316(8): 549. doi: 10.1007/s00403-024-03331-3.

[16] XUE H, CHEN J, FAN W. Assessing the causal relationship between immune cell traits and depression by Mendelian randomization analysis. J Affect Disord, 2024, 356: 48-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.006.

[17] RUAN X, CHEN J, SUN Y, et al. Depression and 24 gastrointestinal diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry, 2023, 13(1): 146. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02459-6.

[18] SHEN M, ZHANG L, CHEN C, et al. Investigating the causal relationship between immune cell and Alzheimer's disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Neurol, 2024, 24(1): 98. doi: 10.1186/s12883-024-03599-y.

[19] BURGESS S, DAVEY SMITH G, DAVIES N M, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: update for summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res, 2019, 4: 186. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15555.3.

[20] BENJAMINI Y, HOCHBERG Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stati Society Series B: Stat Methodol, 1995, 57(1): 289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x.

[21] RAN B, QIN J, WU Y, et al. Causal role of immune cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Mendelian randomization study. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2024, 20(4): 413-421. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2023.2295987.

[22] WANG C, ZHU D, ZHANG D, et al. Causal role of immune cells in schizophrenia: Mendelian randomization (MR) study. BMC Psychiatry, 2023, 23(1): 590. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05081-4.

[23] VERBANCK M, CHEN C Y, NEALE B, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet, 2018, 50(5): 693-698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7.

[24] BOWDEN J, DEL GRECO M F, MINELLI C, et al. Improving the accuracy of two-sample summary-data Mendelian randomization: moving beyond the NOME assumption. Int J Epidemiol, 2019, 48(3): 728-742. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy258.

[25] HEMANI G, BOWDEN J, DAVEY SMITH G. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet, 2018, 27(R2): R195-R208. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy163.

[26] 冯桦, 简恒恒, 李雪, 等. EGR2调控慢性鼻窦炎伴鼻息肉患者Th17/Treg失衡的分子机制. 遵义医科大学学报, 2023, 46(5): 475-483. doi: 10.14169/j.cnki.zunyixuebao.2023.0064. FENG H, JIAN H H, LI X, et al. Regulatory effect of EGR2 on Treg/Th17 immune imbalance in patients with chronic sinusitis. Journal of Zunyi Medical University, 2023, 46(5): 475-483. doi: 10.14169/j.cnki.zunyixuebao.2023.0064.

[27] 汪倩倩, 董雨萍, 严丽洁, 等. 乳腺癌患者4种不同指标变化及其与病理参数的关系. 实用临床医药杂志, 2024, 28(20): 1-5. doi: 10.7619/jcmp.20242084. WANG Q Q, DONG Y P, YAN L J, et al. Changes in four different indicators and their relationships with pathological parameters in breast cancer patients. J Clin Med Pract, 2024, 28(20): 1-5. doi: 10.7619/jcmp.20242084.

[28] 陈琪, 马欣, 毛楠, 等. 调节性T细胞与慢性肾脏疾病关系的研究进展. 成都医学院学报, 2022, 17(2): 267-272. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2257.2022.02.029. CHEN Q, MA X, MAO N, et al. Research progress on the relationship between regulatory T cells and chronic kidney disease. J Chengdu Med College, 2022, 17(2): 267-272. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2257.2022.02.029.

[29] CEERAZ S, THOMPSON C R, BEATSON R, et al. Harnessing CD8(+)CD28(-) regulatory T cells as a tool to treat autoimmune disease. Cells, 2021, 10(11): 2973. doi: 10.3390/cells10112973.

[30] FERRI S, LONGHI M S, De MOLO C, et al. A multifaceted imbalance of T cells with regulatory function characterizes type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology, 2010, 52(3): 999-1007. doi: 10.1002/hep.23792.

[31] CEERAZ S, HALL C, CHOY E H, et al. Defective CD8+CD28+ regulatory T cell suppressor function in rheumatoid arthritis is restored by tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. Clin Exp Immunol, 2013, 174(1): 18-26. doi: 10.1111/cei.12161.

[32] LI G, LARREGINA A T, DOMSIC R T, et al. Skin-resident effector memory CD8(+)CD28(-) T cells exhibit a profibrotic phenotype in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol, 2017, 137(5): 1042-1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.037.

[33] LONGHI M S, MA Y, GRANT C R, et al. T-regs in autoimmune hepatitis-systemic lupus erythematosus/mixed connective tissue disease overlap syndrome are functionally defective and display a Th1 cytokine profile. J Autoimmun, 2013, 41: 146-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.003.

[34] ZHANG Q, VIGNALI D A. Co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways in autoimmunity. Immunity, 2016, 44(5): 1034-1051. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.017.

[35] ESENSTEN J H, HELOU Y A, CHOPRA G, et al. CD28 costimulation: from mechanism to therapy. Immunity, 2016, 44(5): 973-988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.020.

[36] ANTONIOLI L, BLANDIZZI C, PACHER P, et al. Immunity, inflammation and cancer: a leading role for adenosine. Nat Rev Cancer, 2013, 13(12): 842-857. doi: 10.1038/nrc3613.

[37] LAI Y P, KUO L C, LIN B R, et al. CD28 engagement inhibits CD73-mediated regulatory activity of CD8(+) T cells. Commun Biol, 2021, 4(1): 595. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02119-9.

[38] GRANT C R, LIBERAL R, HOLDER B S, et al. Dysfunctional CD39(POS) regulatory T cells and aberrant control of T-helper type 17 cells in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology, 2014, 59(3): 1007-1015. doi: 10.1002/hep.26583.

[39] WILLIAMS H, MACK C, BARAZ R, et al. Monocyte differentiation and heterogeneity: inter-subset and interindividual differences. Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24(10): 8757. doi: 10.3390/ijms24108757.

[40] SKRZECZYNSKA-MONCZNIK J, BZOWSKA M, LOSEKE S, et al. Peripheral blood CD14high CD16+ monocytes are main producers of IL-10. Scand J Immunol, 2008, 67(2): 152-159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02051.x.

[41] CHEN R Y, ZHU Y, SHEN Y Y, et al. The role of PD-1 signaling in health and immune-related diseases. Front Immunol, 2023, 14: 1163633. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1163633.

[42] FRANCISCO L M, SALINAS V H, BROWN K E, et al. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med, 2009, 206(13): 3015-3029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847.

[43] TANG Q, CHEN Y, LI X, et al. The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 964442. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.964442.

[44] BAI X, CHEN T, LI Y, et al. PD-L1 expression levels in mesenchymal stromal cells predict their therapeutic values for autoimmune hepatitis. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2023, 14(1): 370. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03594-z.

[45] BEKIC M, TOMIC S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the therapy of autoimmune diseases. Eur J Immunol, 2023, 53(12): e2250345. doi: 10.1002/eji.202250345.

[46] VEGLIA F, SANSEVIERO E, GABRILOVICH D I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2021, 21(8): 485-498. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00490-y.

[47] DIAO W, JIN F, WANG B, et al. The protective role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury. Protein Cell, 2014, 5(9): 714-724. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0069-5.

[48] LI B, LIAN M, LI Y, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressive cells deficient in liver X receptor alpha protected from autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 732102. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.732102.

[49] KUMAR V, CHENG P, CONDAMINE T, et al. CD45 phosphatase inhibits STAT3 transcription factor activity in myeloid cells and promotes tumor-associated macrophage differentiation. Immunity, 2016, 44(2): 303-315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.014.

[50] TRIKHA P, CARSON W E, 3rd. Signaling pathways involved in MDSC regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014, 1846(1): 55-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.003.

开放获取 本文遵循知识共享署名—非商业性使用4.0国际许可协议(CC BY-NC 4.0),允许第三方对本刊发表的论文自由共享(即在任何媒介以任何形式复制、发行原文)、演绎(即修改、转换或以原文为基础进行创作),必须给出适当的署名,提供指向本文许可协议的链接,同时标明是否对原文作了修改;不得将本文用于商业目的。CC BY-NC 4.0许可协议详情请访问 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0

首页

首页

下载:

下载: